Introduction

Can you imagine how much more dangerous it would have been working in a factory 200 years ago, in comparison to what it’s like now (in the UK at least)?

Everything is far from perfect nowadays, but we all understand that many years ago industrial safety was seen very differently. We’ve heard about how many people were killed while building a famous bridge, or a tall building. We know that it was much more common for people in factories to lose arms or fingers.

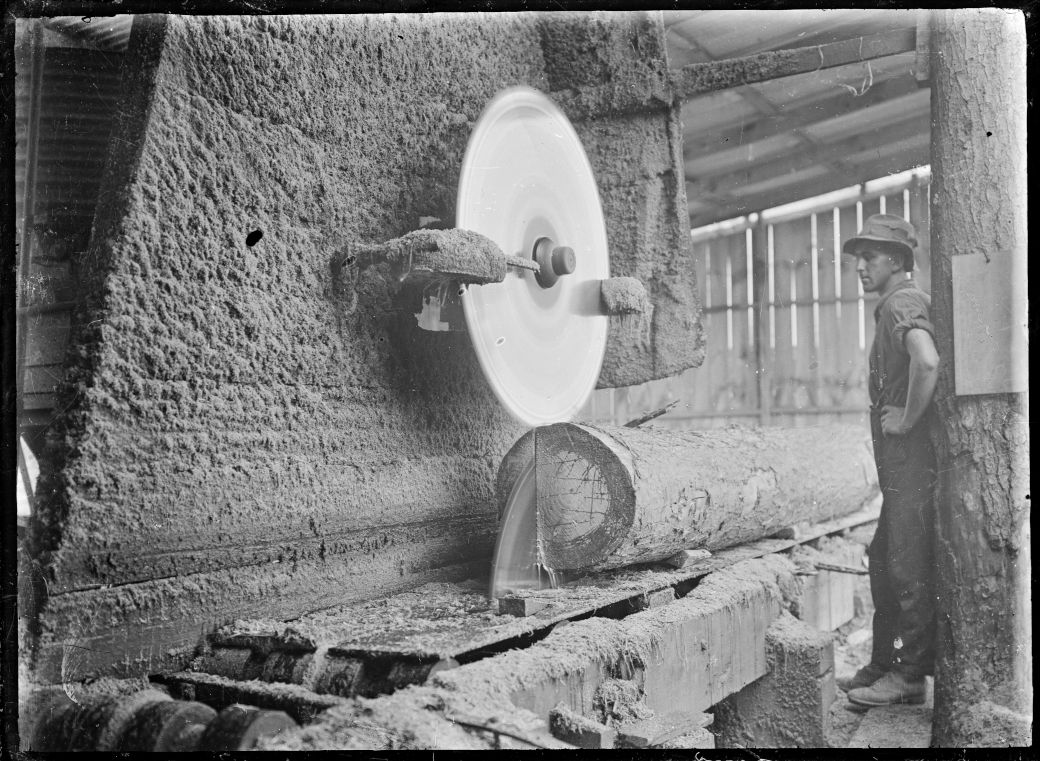

Once upon a time we might have told a worker to be careful when using a dangerous piece of equipment (like in the photograph). We might have provided a bit of training, but that would have been all. If they were later hurt through their own carelessness we’d have considered it unfortunate, but not our fault. We’d have called this an accident.

And we’d perhaps have seen the world as unpredictable, and that sometimes a set of unfortunate events would happen to line up, with people getting hurt as a result. That might have made us sad, but we’d have talked about unfortunate tragedy.

We’d have seen these accidents, these deaths and injuries, simply as the price of progress, as a price worth paying for our way of life.

But in modern times – at least in developed countries – almost everyone can be pretty sure that they’ll not die or be seriously injured at work.

Nowadays we expect that if an employee dies or is badly injured, then the company that employed them will be in trouble. And if an unpredicted event means someone gets hurt we’ll want to know why it wasn’t predicted. There will be difficult questions asked. Investigations will be carried out. There may be major penalties or even criminal prosecutions.

Of course poor practice continues, and there are still bad employers, and there are dangerous jobs with good employers, and we still use dangerous equipment, but the point is that we think about this differently to 200 years ago.

Of course you know why I’m saying all of this.

Two hundred years ago, if I’d said that I really believed that I was working for a situation where nobody should be badly injured and nobody should die at work, people would have thought me overly idealistic. Now it seems like a very reasonable objective.

So here’s a really really big question:

If it doesn’t sound idealistic to say that I think that nobody should be seriously injured or killed at work… why then does it sound idealistic when I talk about what happens on the way to work? Why does it sound unrealistic to say “I genuinely think that nobody should be seriously injured or killed travelling to work?”

Why do we think about industrial safety and road safety so differently?

Systemic safety

This is a conversation about systemic safety – about making a system safe. We’re quite used to thinking in systemic terms (about a whole system) when we think about industrial safety, but it’s still an alien idea for most people when thinking about our roads.

Systemic safety means blaming injury or death on the system first, even if the person being injured was also at fault in some way. When someone is hurt we expect investigations and questions. We’ll want to know about causes. We’ll look at an overall working environment.

We expect a company, and the wider system, to plan for the fact that people will make mistakes, will be stupid or incompetent, will be impatient or selfish. We’ll expect the company to predict all but the most unlikely chains of events, and to mitigate against these events hurting people.

We’ll not just expect a company to try quite hard to keep people safe. Instead we’ll expect a company to do what it takes to keep people safe.

We did this with industrial safety. We can do the same on our streets – if we choose to.

So here’s another really big question:

If we REALLY want to completely prevent injury and death on our roads, while still allowing motor vehicle use, what would we have to change?

We’d need a bit of a revolution wouldn’t we? We’d not be thinking just about tweaking the existing system. We’d be thinking about fundamental reform of the whole system.

As far as I see it this idea of fundamental system reform is the starting point for understanding a systemic approach to safety on our roads and streets… knowing that we’re talking about doing what it takes, about CHANGING THE WHOLE SYSTEM… about creating a new system which isn’t just a bit better but which is genuinely as safe as possible.

So far so good, but if you’re new to this then please know that you’ll need to look very carefully to find properly good things to read if you want to find out more. You need to know that it’s very common to find that old-style road safety approaches have been relabelled, by old-style road safety professionals, using the new language of systemic safety, and particularly using the title ‘vision zero’.

It should also be said that systemic safety isn’t something new, and old-style systemic safety thinking is still influencing some of our current street design. This drives a vision of a world where pedestrians will be safe from traffic because we’ll all spend our lives on elevated walkways or in underground tunnels – kept apart from the traffic as much to facilitate traffic movement as for our safety.

So how to tell the difference? Well you’ll know that you’re dealing with a traditional safety approach, even if it’s given the title ‘vision zero’, if what you’re reading is mostly about:

- small iterative improvements to how major roads are designed,

- small iterative improvements to features like posts or crash barriers or vehicle construction to reduce injuries,

- speed limit changes, and

- information campaigns to ask people to follow the rules and to be careful.

To be clear, I’m not criticising any of the above pieces of work outright. I’m in no doubt that the many small but iterative improvements to road and vehicle design have made a huge difference to safety. If I ever have something bad happen while driving on a motorway I’ll be pleased to find my life saved by the design of the vehicle or the crash barrier. Each of these threads of work will play some part in a systemic safety approach BUT any work on safety which assumes that the basic system is already fit for purpose is, by definition, not a systemic safety approach.

Systemic safety – key ideas

So we’ve already covered at least three key ideas:

The system can be fundamentally changed – A systemic safety approach demands that we’re open to changing fundamental aspects of the system, not just to trying to improve the existing system little by little.

Injury or death indicates a faulty system – If injury or death occurs, even as a result of human error, it becomes important to question where the system failed, and TO CHANGE IT so that this isn’t repeated.

A good system deals with real human behaviour – People make mistakes, and they sometimes behave badly. A good system doesn’t assume good behaviour or a lack of mistakes, but instead prevents human mistakes or bad behaviour from causing severe injury or death.

On this last idea it’s worth saying that when thinking about systemic safety we may also ask whether individual people are at fault. Systemic safety doesn’t mean ignoring guilt or poor behaviour – it means asking what we need to change so that when people behave poorly this doesn’t cause severe injury or death.

Now let’s add two further key ideas:

No level of death is a price worth paying for the convenience of the majority – This is as simple as it sounds. Death on our roads isn’t ‘just one of those things’ – isn’t a price worth paying. We really GENUINELY need to be working to prevent it – like we work to prevent deaths at work. We genuinely need to DO WHAT IT TAKES not just to try very hard.

A good system decreases both injury frequency and injury severity – A systemic safety approach does not only try to reduce injury frequency, but also the severity of injuries.

Technical decisions are political acts

So the theory sounds great, but before we get too enthusiastic I think there’s a problem we need to notice. At least we need to notice this if we live in countries like the UK. And it’s convenient to add this here as one more key idea which defines a systemic safety approach:

Street and road design isn’t a neutral act. It’s not even possible to be neutral when we maintain a road or street. Even just keeping things as they are is a political act. Any street design provides advantage to some at the cost of disadvantage to others.

Here in the UK we make a big mistake. We consider road and street design as a technical matter. Those who have classes at university about it, pick up a manual about it, or read guidance about it, learn that they should follow (politically neutral) good practice. The problem is that much of this good practice isn’t politically neutral at all.

It might seem fair to argue that it’s the job of those with political roles to make policy – and that this shouldn’t be left to technicians. I’d agree.

What this means, in practice, is that those with political roles have to get involved in technicalities – and not just policy. These people can’t just decide that our policy is that our streets should be safe, or that they should be made friendly for walking and cycling – leaving the decisions about how to achieve this to the technicians. Because if the technicians continue to work within the basic ideas that they’ve been taught to apply, which their managers expect them to base their work on, which their jobs depend on following, then what they design or maintain will, broadly, continue to support the status quo.

This is another way in which ‘systemic safety’ demands that the whole system has to be open to change.

Are other countries working on this already?

This all sounds difficult – are there other countries already working on this whose efforts we might copy?

The two most interesting projects that I’m aware of are in the Netherlands, and in Sweden.

The Dutch policy is called ‘Sustainable Safety’ and the Swedish approach is ‘Vision Zero’. This title is perhaps the best known, having been used internationally.

As regular readers will know, it’s Dutch practice that I’m most familiar with. I’ll explore details about this in the article ‘Rethinking road safety – Part 2’ where I’ll be asking whether we could copy Dutch policy and practice.

Conclusions

To summarise the arguments I’ve made in this article…

-

A systemic safety approach is fundamentally different to a traditional safety approach. Thinking about how safety at work has changed over the last couple of hundred years reminds us that it isn’t silly idealism to try to work toward a situation where people no longer die on our roads.

-

Systemic safety relies on the idea that we’re happy to change fundamental aspects of how our system works. Any work that assumes that the basic system is a sound one, is by definition not a systemic safety approach. When thinking about this we need to notice that old-style safety work is often labelled with the new language of systemic safety and ‘Vision Zero’.

-

Real systemic safety/‘Vision Zero’ work might occasionally employ public information campaigns, but this is a tiny element. Real systemic safety work assumes that people make mistakes, and that they will always be careless, selfish, stupid, and simply human. While there may be a little bit of worth in telling people to behave nicely or to be careful, we know that this work is almost irrelevant in comparison to the wider systemic change that’s needed.

-

We’ll never be able to deliver a systemic safety approach while we consider street design to be a technical matter, best left to technical experts. All street design, and even maintenance which preserves the status quo, is a political act. If we’re serious about this then those with political roles have to move beyond fluffy policy, getting involved in design decisions – in debating and deciding how our streets are going to work in more detailed terms if they are to become safe.

Footnote on language

(sustainable, systemic, systematic)

I’ve chosen to use the phrase ‘systemic safety’ – but others also write about ‘sustainable’ or ‘systematic’ safety – or about ‘safe systems approaches’. I’m pretty clear that the Swedish ‘Vision Zero’ approach, and the Dutch ‘Sustainable Safety’ policy, can both be described as systemic safety policies.

One of the most recent Dutch documents comments on the use of the word ‘sustainable’ in regard to the Dutch policy (coincidentally reminding us that we’re at least 35 years behind them in their thinking):

When the vision originated, the name ‘Sustainably Safe Road Traffic’ was derived from the Brundtland report of the United Nations (1987) on sustainable development, which was extremely relevant at the time. It was defined as ‘a development that meets the current demands without impeding the possibilities of future generations to fulfil their needs’. Sustainable Safety builds on this definition… …using what is also referred to as ‘inherently safe’ design… In the past, ‘inherently safe’ was not included in the name of the vision, even though it actually better expresses a system approach. Sustainable Safety has become a familiar ‘brand’ for traffic professionals… …that, similar to the Swedish Vision Zero, is taken as an effective and professional way of improving road safety systematically.

The title ‘systematic safety’ is also quite helpful in some ways, but I use the phrase ‘systemic safety’ because I think it explicitly makes the link to the idea of a safe system.

See also

- Rethinking road safety – Part 2 [To be published soon]

- Some maps showing ‘just one year‘ of death and injury on UK streets.

- https://www.swov.nl/en/facts-figures/factsheet/sustainable-road-safety

- https://www.swov.nl/en/publications/swov?mfulltext=sustainable%20safety

- Read everything like a book – New here? This is a suggested reading order for all the articles on this site.

Comments…

- I welcome comments, even if you want to tell me (politely and constructively) that you disagree. Scroll below to view what others have said.

If you landed here from a Twitter link on a mobile device you may need to press ‘Leave a comment’ below to see the comments on this article – or you can reload the page to see them.

You may be planning this for part 2 but: systemic safety also has to include the larger holistic picture, such as public health.

For example, in the UK there is a breed of engineer who believes in making cycling as difficult as possible in order ‘to make it safe’. Those are the sort who install as many barriers as possible to cycling, because they believe this will make cyclists safer. It will prevent the rare case of someone ‘flying out into traffic’ from a pathway, for instance. Or so they think.

Anyway, the fact that these barriers discourage cycling does not worry them. The public health (and urban design, etc) implications of discouraging cycling are not their concern. If fewer people choose to cycle, that’s ‘safety achieved’ in their book.

But of course a true systemic safety approach recognises that discouraging cycling and encouraging driving leads to worse public health outcomes and more injuries and deaths.

LikeLike

Hi Matt

That’s an excellent point. I’ve tried to talk a bit in part 1 about how the solution isn’t to lock walking and cycling away – on bridges and in underpasses. I’d not thought to present this (in this article) as a health issue, but that’s certainly a good way to look at it. Part 2 is already mostly written, and it’s about the Dutch Sustainable Safety approach – and I’m certainly making the point that they properly support walking and cycling… but I’ve described this as being about recognising that people belong on the streets and about basic quality of life.

One way or another – something we need to emphasise is that a systemic safety approach can’t be at the expense of ordinary life on our streets.

LikeLike

I can recall an interview on Radio Scotland a few years ago of Norman Armstrong of Freewheel North, who has, for years, been advocating the kinds of things you are. He had written an article about making public spaces more ‘permeable’.

The interviewer began by saying, “Roads are for cars. That’s why we have them”.

Norman replied by pointing out that we have had roads for millennia, but cars have existed for a little over a century. Roads are to enable people to get from one place to another and, for most of human history, that was, and still is, by WALKING.

This ‘reframing’ proved very difficult for the interviewer to deal with!

So, while I agree with your analysis about improving safety, I think we also have to assert the right that roads are public spaces for ALL of us, and, since all of us walk for most of the time, then roads should be viewed as primarily for pedestrians. The usual indignant response is, “We pay Road Tax”. Not withstanding the fact that there is no ‘Road Tax’, roads are paid for and maintained from general taxation. My taxation, as a non-car driver, contributes to roads, so I have a right to a say in the use of roads. It was ‘no taxation, without representation’ that started the American War of Independence.

LikeLike