Design Details 2

A quality checklist for continuous footway

Continuous footway can be used to significantly prioritise and protect those on foot and bicycles, people with less skill in negotiating moving traffic, and people with a wide range of disabilities. But continuous footway only does these things if it’s well designed. Poor quality continuous footway can create an environment which can be really difficult for many of these same people.

I support the opposition of various people, and most obviously groups representing those with a visual impairment, to some of the designs currently being introduced in the UK.

I’ve often been asked about how continuous footway should be designed, and I’ve grown tired of the continual re-inventing of the wheel that I can see – when the Netherlands has been refining these designs for decades to make sure they work well for everyone. Therefore this article proposes a draft quality checklist for ‘continuous footway’ designs. It is aimed at a UK audience, but might apply in many other countries where continuous footway is being introduced. It’s intended for designers and technicians, and to prompt discussion among experts, and (if I’ve got it right) to act as a reference.

The articles “I want my street to be like this…” and “Design Details 1” offer a much better introduction to continuous footway than you’ll find here. Unless you already care about the design of continuous footway you are likely to find this particular quality checklist as dry and boring as any other quality checklist – although you may find the images after the checklist to be helpful guides to what good/failing designs look like.

Lots of people are now being referred to this checklist, but I continue to welcome comments. Please keep an eye on it because I may update it in response.

The checklist necessarily has lots of words, with the accompanying images coming later in the article. To keep things interesting here are images of three designs which meet the checklist conditions…

…and images of four POOR designs which FAIL the checklist conditions and which should be avoided.

Disclaimer & checklist status:

It would be negligent for anyone to implement a design on the basis of this article without undertaking a full, independent, and competent assessment of the safety of that design. This article presents my layman’s understanding of what makes for good (safe) continuous footway, based on my personal observations of Dutch designs in place within the Netherlands (and Danish designs in Copenhagen). It is not based on any qualification or position I have, or on reference to any agreed set of standards. I have no direct evidence that using these designs in the UK will be safe. With the introduction of any novel design it is also essential that the performance of the design is assessed in terms of safety, and in other respects, after it is installed, and that the design is rectified or removed if it fails at that stage.

CONTINUOUS FOOTWAY QUALITY CHECKLIST

Version 1.2 – January 2020

A – fundamentals

‘Continuous footway’ is a term used to describe situations where the footway1 of a major street2 continues alongside the major street, across the entrance to a minor street2 or other minor access. This checklist proposes minimum conditions for continuous footway designs in the UK. For continuous footway designs to be safe they must meet at least these conditions.

- Anything which looks or feels like a footway to people walking3 on it should be designed so that it is very clear, to people in vehicles, that it is a section of footway and not a section of carriageway, even if people are allowed to drive over this footway. The safety and proper functioning of ‘continuous footway’ depends on this clarity.

- The safety and proper functioning of ‘continuous footway’ requires physical constraints to bring vehicle speeds to a walking pace. There must be short distinct ramps4 at either side of the footway that force anyone driving any normal motor vehicle to slow to a walking pace when driving up onto the footway. A wider set of design features must also be in place in order to control the speed of any vehicles not suitably slowed by such ramps.

- The safety and proper functioning of the ‘continuous footway’ must be created by the overall physical design, with minimal reliance on any accompanying road markings, signs, or laws.

- The footway design, the street design, and traffic conditions experienced near the footway, must allow people driving to see the footway and understand how to deal with it safely and appropriately and with sufficient time to react.

- The safety and proper functioning of ‘continuous footway’, on the basis of the points above, must not be undermined by too great a volume of vehicle movement over the footway, or by queues of vehicles waiting on the footway (meaning that it must be used only in situations where traffic is, or will be, limited).

- Only one direction of motor vehicle usage across the footway must be possible at a given time, either through ‘one-way’ regulation, or by physical restrictions to the width of space available.5

- The design must also meet the further ‘design conditions’ in section B, and if the major street includes a cycle track also the ‘cycle track conditions’ described in section C.

- Continuous footway should only be used where it will also mark a transition, for people driving, from a more major carriageway to a more minor carriageway (or access) where the physical design of the streets (or access) create lower speeds than on the more major carriageway.

footnotes:

1 ‘Footway’ is used here as a more technical and specific term for what is usually called ‘the pavement’ in the UK

2 ‘Major’ and ‘minor’ here are intended to refer to the relative status of the two streets involved, not their level of classification in the wider road network

3 ‘Walking’ is used as a general term to keep the language in the checklist simple, and it should be assumed to also be referring to others appropriately using a footway, such as people using a wheelchair, mobility scooter, and children on balance bikes.

4 The ramps may be omitted at a very minor access which is rarely used, such as to a private driveway for parking one vehicle, provided vehicle speeds are equally restrained by other physical features.

5 In other words, if two way traffic is allowed the entrance should be so narrow that someone driving a vehicle into the minor street must wait for any vehicle being driven out of it to fully exit (or vice versa) – so pedestrians are not at risk from vehicles moving in both directions at the same time.

B – design conditions

The fundamental points A1-A7 above are likely to require a design which complies with the detailed design conditions below:

- Other than at the ramps (which facilitate vehicle access between carriageway and footway), it must be completely clear which sections of the design are footway, and which are carriageway.

- The footway must be visually distinct from the carriageway.

- The appearance of the footway, and specifically its overall colour and texture, must not substantially change at or near the place it crosses the minor road.

- The line defined by the kerb at the edge of the major road, and the access ramp to the footway, should be aligned, so that the ramp continues the kerb line without any significant bends or inset into the footway area.

- Any linear road markings, or other linear design features, which follow the edge of the major road, should continue substantially unchanged across the end of the minor road (this includes the design of any on-street cycle lane).

- The surface of the footway should be flat and level (in relation to the wider street incline and crossfall rather than in an absolute sense – so any overall incline matches that of the surrounding infrastructure)

- The ramps must provide a gain in height of at least 100mm, within 800mm or less [NB: this is a DRAFT condition which has values which are based on guesswork and Dutch standards, and these would need to be checked against UK vehicle designs – I particularly want comments on these values].

- If parked vehicles will be present on the major road then the ramp allowing access to the footway from the major road, and the kerbs immediately on either side of this ramp, should be in parallel to the line defined by the outside of these parked vehicles (see annotated images later).

- There must be no road markings on the footway, nor the ramps. If for safety (or to avoid damage to vehicles) it is the case that a given design will require road markings in order to instruct people how to behave or to highlight the existence of the ramps, then it is not a good design, or it is a design which is being used in an inappropriate location, or a design which requires appropriate changes to the wider environment so that this is no longer the case.

- Any signage directed at those considering entering or leaving the minor road should be close to the ramp between the footway and the beginning of the carriageway of the minor road (rather than in the general footway area or close to the ramp to the major road).

- There must be physical features to prevent parking on the minor street at a location which is too close to the footway, where it would obscure the view from a vehicle (approaching along the minor street) of people on the footway.

C – cycle track conditions

Where a cycle track6 runs in parallel to the footway beside the major road, conditions A1 to A6 are unlikely to be met unless the design also complies with the detailed design conditions below:

- At the continuous footway the cycle track must run within the area between the ramps (in the same way that the footway is between the ramps – and rather than it being between the ramp and the carriageway of the major street)7

- The cycle track must be visually distinct from both footway and carriageway.

- The cycle track must be continuous (i.e. must not stop and start on either side of the continuous footway feature).

- The appearance of the cycle track, and specifically its overall colour and texture, must not substantially change at or near the place it crosses the line of the minor street.

- The cycle track must continue in a line which is generally parallel to the direction of the major road. Any bending of the track toward or away from the major carriageway should be gentle enough to avoid undermining the visual impression that it continues with this generally parallel line.

- Any markings, signs, or other design features on or associated with the cycle track, must not undermine the visual continuity of the footway, and must not imply priority for those driving across the track. If for safety (or to avoid damage to vehicles) it is the case that a given design will require such road markings, then the overall design it is not a good design, or it is a design which is being used in an inappropriate location, or without appropriate changes to the wider environment.

- The cycle track must be separated from the footway by an appropriate kerb of at least 50mm height, which (at the continuous footway) has an angled surface so as to allow slow speed access to and from the cycle track by bicycle from the major or minor road or access.

Footnotes:

6 For the purposes of this checklist a cycle track is an area provided for cycling alongside the carriageway which is physically divided from the carriageway.

7 Take note that conditions B5 and C1 have consequences for the design of cycle lanes protected by ‘light segregation’ features (i.e. where the cycle lane is structurally part of the carriageway rather than being offset from it). These conditions taken together would generally prevent the provision of such a lane where there would be a gap in the light segregation at the continuous footway. The gap in the light segregation features (necessary to allow vehicles to cross the lane) risks creating the appearance of a road end, thus undermining the safety of users of the footway.

Images of good designs

These three designs comply with the checklist.

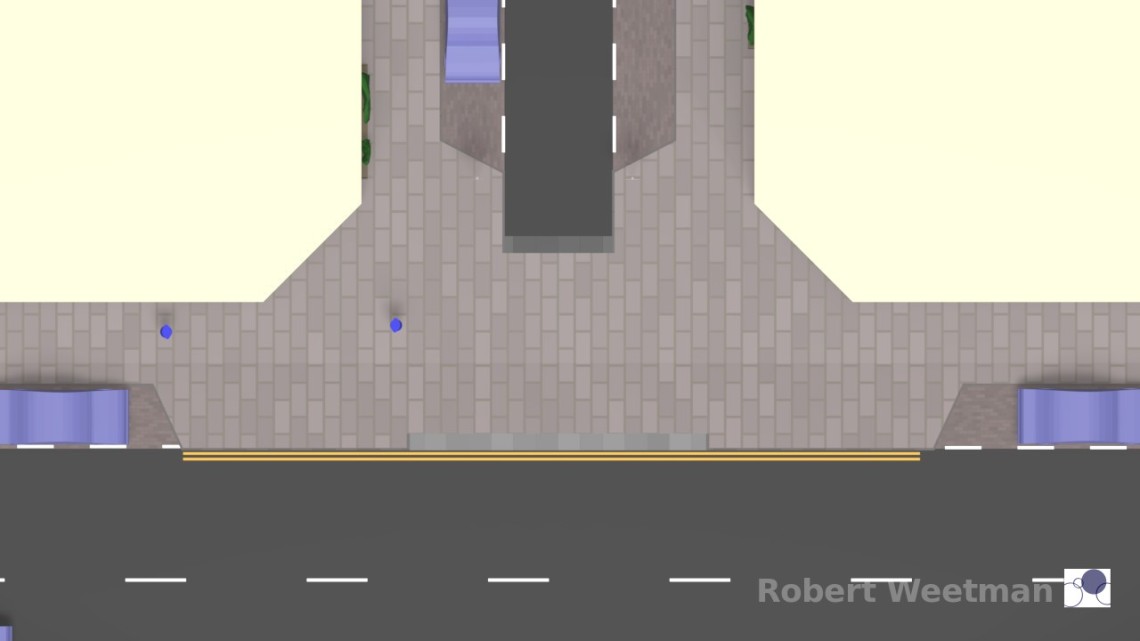

D1: Footway, with parking on major street

Take note of the following: It is clear that the footway is footway. There is no ambiguity in this design. The one-way side street’s carriageway is very narrow, restricting speed. The ramp beside the major street’s carriageway sits in a line which is parallel to the outside edge of the parked vehicles, and both ramps are very short, steep, and distinct. There is no break in the double yellow line, and nothing curving inward from this which might suggest a road end. The footway is not the same colour as the carriageway. There are no road markings on the footway or ramps.

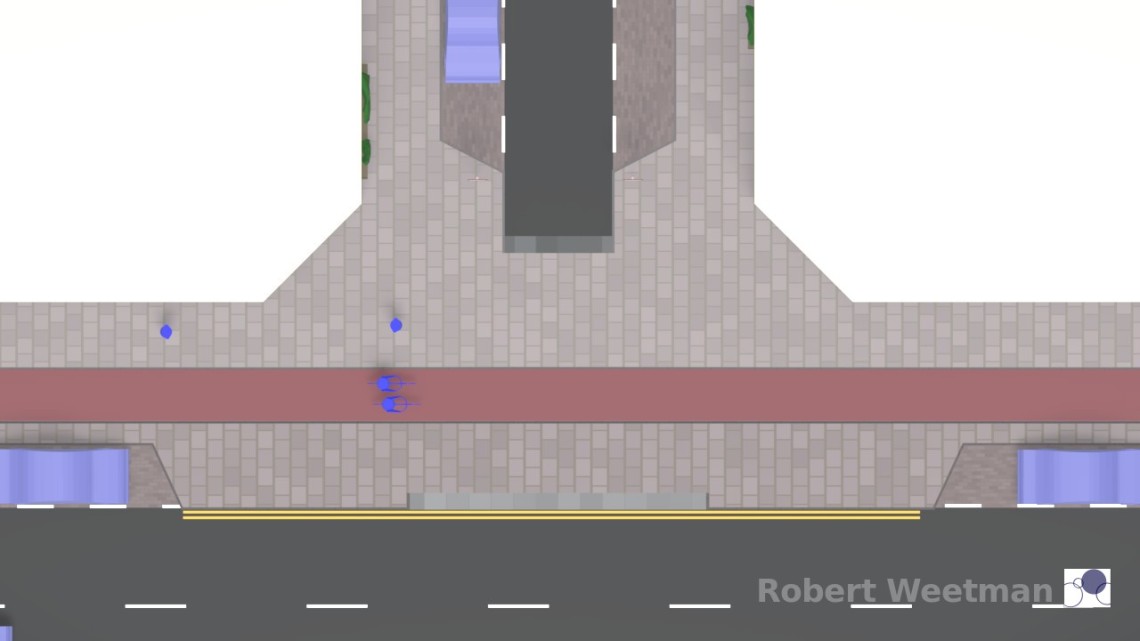

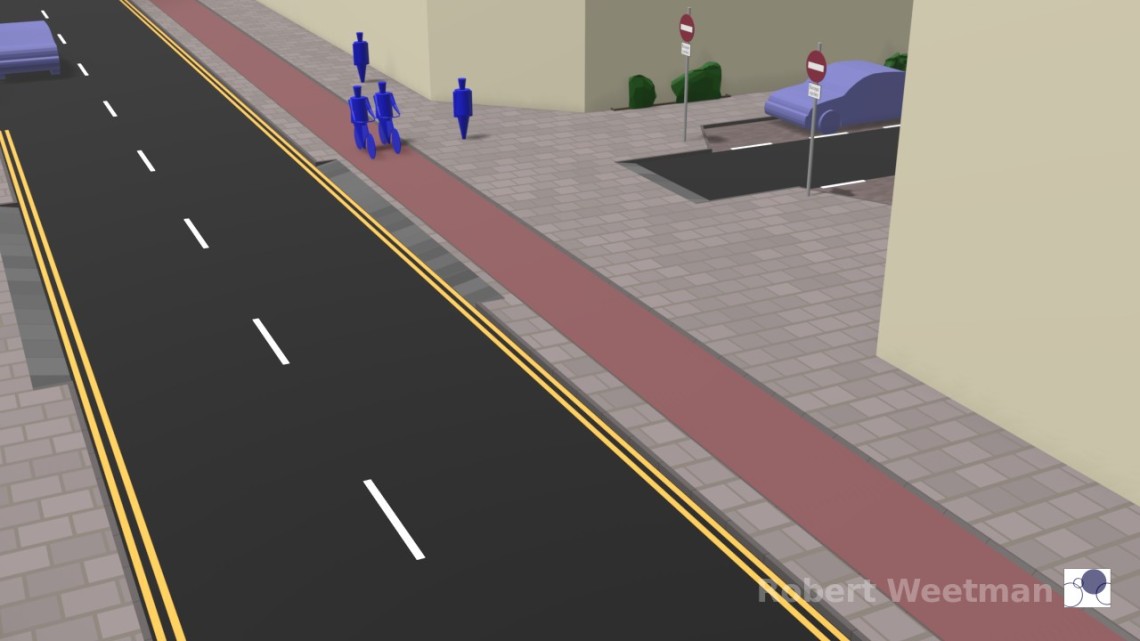

D2: Footway and cycle track, with parking on major street

This is fundamentally the same design as D1, but there is a cycle track. Take note that the cycle track is unbroken, has no changes in its path which would undermine the visual continuity of the footway or suggest a road end, and that it is visually distinct from the footway and carriageway.

D3: Footway and cycle track, without parking on major street

This design shows the situation where no parking takes place on the major street. This design passes the checklist conditions, but may be problematic when used for a side road entrance because the drivers of vehicles turning into the side road from the nearest lane cannot easily see people approaching from behind. Design D3b may improve matters.

D3b – D3 design but with additional minor bending of the cycle track

This design is similar to D3 but with some minor bending of the cycle track, aiming to increase separation from the carriageway. This design passes the checklist conditions provided this bending is not so great as to imply a road end (condition C5).

Additional images from the above models are provided at the foot of the article.

Design failures

The following four designs fail against the checklist.

D4: Footway is too insignificant

This design fails condition A1 because the continuous footway is much too narrow, meaning that it is visually much less significant (fails condition B2) in comparison to the overall visual presence of the carriageway of the minor road.

There is also a failure to significantly narrow the carriageway of the minor street well before it reaches the footway, allowing a parked vehicle to obscure the view that someone driving out of the minor street should have of people on the footway (condition B11).

D5: Confused visual signals

This design fails condition A1 and B1 (it is not clear whether this is footway or carriageway or a hybrid ‘shared space’). This results partly from it failing conditions B3 (lack of visual continuity due to significant surface changes), B5 (yellow lines mark the carriageway junction rather than continuing unbroken), and B9 (road markings on what might otherwise be understood as footway).

The effect of adding road markings to try to make the design safe is that the most important message, which is “here is a footway” is buried under multiple competing messages, many of which imply that this is a section of carriageway.

It also fails condition A6, because it allows simultaneous two way traffic, significantly increasing the risks to those cycling and walking.

D6: Confused visual signals, missing ramps

This design fails condition A1 and B1 (it is not clear whether this is footway or carriageway or a hybrid space which is a bit of both). These failures arise primarily as a result of the design failing condition B3 (lack of visual continuity due to significant surface changes). The break in the visual continuity of the cycle track (conditions C3 and C4) significantly increases the impression that this is a section of carriageway (despite the white markings). The lack of visual continuity of the footway is significant, despite the fact that the change in surface material is further from the minor street than in design D5. This makes a larger area look like it may be for driving on, and significantly undermines any message that it is a section of the footway.

The lack of the ramps is a very major failing (condition A2), very significantly increasing risks to those walking and cycling because people can now drive onto this space at speed.

As above, this design also fails condition A6, because it allows simultaneous two way traffic, significantly increasing the risks to those cycling and walking.

D7: Raised table creating shared space

This design fails condition A1 because the addition of the raised table on the carriageway means it is not clear what is footway and what is carriageway (also conditions B1, B2, B9, C2, C3, C4, C6).

It fails condition A2, because ramps to the area are too distant from the space where people walk (rather than being alongside the footway), and are not steep or sharp or distinct enough (also condition B7), therefore not slowing traffic sufficiently.

It also fails other conditions (A6, B4, B5, C3, C7).

Adding a raised table to the carriageway generally is not compatible with the creation of a continuous footway, however there may be other very different situations where raised tables are appropriate at a junction – for example, in quiet residential streets (see article ‘I want my street to be like this…‘ ).

Discussion

In reading the checklist the following should be understood:

‘Continuous footway’ is a relatively new term which arises from the need to add new infrastructure in existing locations. It is not normally used to describe existing locations where footway can be driven over to reach a residential private driveway or minor access, but in design terms there is no clear division between ‘continuous footway’ at a street junction and the design of footway at this kind of minor access. Thus the checklist is intended to apply to both situations. There are many existing examples of footway design at private accesses which create poor conditions for footway users. Good quality footway designs at these locations would comply with the conditions in this checklist.

One purpose of this checklist is to highlight that hybrid designs, with only some features of continuous footway, are undesirable, and that they may be unsafe. This checklist is written in such a way that it specifies that if any users of the footway, including those with visual or cognitive impairments, or the very young, are likely to interpret a design as a continuation of the footway then this checklist should be applied – or the design should be changed so this is no longer the case.

The checklist is not intended to outlaw other different methods of prioritising the movement of people walking or cycling across a side road – provided they do not give the impression to footway users (including users of any associated cycle lane, track, or path) that the footway (or cycle infrastructure) continues unbroken.

Other level ‘side road entry treatments’

The checklist raises difficult questions about those “side road entry treatments” which create a surface level with the footway, but with no pretence that they continue the footway. Here’s an example from London.

This is clearly NOT a continuous footway. It is what tends to be called a side road entry treatment. There is little doubt (for most users) that this is a section of carriageway.

I’m not personally sure that this is a good thing to do – I don’t know whether it’s a good design or not – but I do know that this is not a continuous footway design.

I’ve explained where I think the line is which divides ‘acceptable’ and ‘unacceptable’ continuous footway designs – in the top condition in the checklist (A1):

“Anything which looks or feels like a footway to people walking3 on it should be designed so that it is very clear, to people in vehicles, that it is a section of footway and not a section of carriageway, even if people are allowed to drive over this footway.”

I would apply 3 tests to a side road entry treatment design like this:

- Do the wide spread of ordinary users of the footway interpret this as footway, or recognise it as carriageway?

- Do people with visual impairments interpret this as footway, or recognise it as carriageway?

- Do children of 5 years old interpret this as footway, or recognise it as carriageway?

If people driving are going to interpret this as carriageway (which seems quite likely – but perhaps should be checked) then it is essential that all of the above footway users recognise it as carriageway. If they do, that’s fine – it’s a side road entry treatment which may or may not achieve anything, but which isn’t covered by my proposed checklist. If any or all of the above people interpret this as footway, then in my view the job needs to be done properly – making it proper continuous footway and ensuring it passes this checklist.

Why do we need this checklist?

It is my belief that the only safe way to introduce continuous footway designs in a UK environment, is to ensure that they are of high quality. In places where the use of continuous footway is common, and people are familiar with them, then more compromised designs might still be safe. But in the UK the use of continuous footway is very rare.

To my mind what this means is that we should carefully copy the proven designs used elsewhere, with the Netherlands being the obvious choice. And we should take note of what a good quality Dutch design would look like, and of why it looks that way.

Let’s put it like this: if, instead, we were introducing zebra crossings into a country which had never used them, we’d want a very high quality version of a zebra crossing. We’d look to a country where zebra crossings are standard. We’d create a really good copy of one of their really good zebra crossings. We’d want whiter paint, more obvious stripes, brighter lights, a narrower stretch of carriageway, and so on. I’ve heard it argued that the UK isn’t ready for proper Dutch continuous footway, and that ambiguity makes things safer. But it would be ridiculous to argue that – in a country unused to zebra crossings – the safest designs would be ones which were ambiguous. It’s just as ridiculous to make that argument about continuous footway.

Additional images

These are additional images – from different angles – of the designs already shown above.

Good designs

D1 (good): Footway, with parking on major street

D2 (good): Footway and cycle track, with parking on major street

D3 (good): Footway and cycle track, without parking on major street

D3b (good): As D3 but with minor bend in cycle track

Design failures

D4 (failure): Footway is too insignificant

D5 (failure): Confused visual signals

D6 (failure): Confused visual signals, missing ramps

D7 (failure): Raised table creates shared space

Checklist change log:

Version 1.0 – new, October 2019

Version 1.1 – minor change to wording of condition A7 for clarity, January 2020

See also

- I want my street to be like this (detailed discussion of Dutch residential local access streets – the areas which are behind the gateway created by continuous footway)

- Design details 1 (a longer explanation of what makes continuous footway work, what it is used for, and a detailed explanation of why ambiguity in this kind of design is a mistake). INCLUDES STREETVIEW LINKS to examples of continuous footway designs used in the UK, and examples from the Netherlands.

External links

- Who is liable from Ranty Highwayman might provide some thoughts about liability when pursuing novel designs, not least because he uses continuous footway as an example.

Comments…

- Scroll below for comments.

Please read on below as there are some substantial comments, adding important ideas and information, including from ‘Hanneke28’ who provides useful details about the Dutch situation, direct from the Netherlands.

If you landed here from a Twitter link on a mobile device you may need to press ‘Leave a comment’ below to see the comments on this article or you can reload the page to see them.

Thank you for a very clear exposition of the topic. Hope the traffic engineers and designers are taking note!

LikeLike

https://photos.app.goo.gl/1jNGCU89hp3T9swY9

An example from Sydney, Campbell St off Missenden Rd, where they seem to have it right. Can see before and after (and during) on Google Streetmaps.

LikeLike

Thanks for sharing. Here’s the Streetview link: https://goo.gl/maps/KXDhpnfLxL84HdGG8 – I’d like to see much steeper/shorter ramps (first impressions from Streetview are that those wouldn’t slow you down) – and I think something to narrow the side street before it meets the footway – as a really powerful visual signal to people that something different happens here.

LikeLike

Yes, the ramp is very shallow and the splayed side ramps also encourage (?) drivers to make a quicker turn. But a steeper ramp might make access from the bicycle lane to the side street more difficult. That was my initial interest in this intersection, as an example of a very smooth transition across the kerb line for cyclists. Too many kerb crossings here have lips or jump-ups that discriminate against cyclists. But maybe they have gone too far in this case and the ramps could be steeper.

LikeLike

Ideally ramps should be 1,7 m long and sinusoidal. Otherwise they’re not really cycle friendly, but unfortunately very often there’s only space for shorter ramps.

LikeLike

My thinking is that you do not need the ramps to be cycling friendly – or at least they only need to be friendly enough for what they will be used for, which is very slow speed access/exit from the side road. And I’d 100% lose cycle friendliness at the ramps to have pedestrian/cycling safety from vehicles. Nobody will be cycling across these ramps at speed – nobody will be driving across them at speed – and if they are then you put the continuous footway in the wrong place.

LikeLike

In some areas tarmac is the predominant material for footways as well as as carriageways. I wonder if the checklist needs to be more explicit about the visual differences between footway and carriageway. It’s an obvious one when the two are routinely in contrasting materials but when they’re not, should a third material/colour be used, and how does this reinforce the continuity rather than looking like a third, ambiguous, surface? Perhaps distance of this new surface back from the junction needs to be longer than in other scenarios?

LikeLike

An excellent question. I’ve tried to balance simplicity against adding too much extra detail – I guess partly with the idea that there should be some additional explanation if necessary (after rather than in the checklist). I completely agree – where it’s necessary to use a new material (so that there’s contrast) then it needs to extend well away from the site we’re interested in (so it’s continuous near the site).

LikeLike

On the need for visual continuity, I think you need input from an accessibility expert as the one I once (briefly) discussed this layout with still insisted upon tactiles being used to alert blind pedestrians to a possible danger. This could disrupt the visual continuity you’re looking for.

(I’m sure I’ve also seen tactiles used on Dutch examples – a sort of ‘T’ laid on its side with the stem pointing down the approaches and hte head truncated so it doesn’t cross the whole of th epavement, maybe only about 4 tactiles/1.6m long).

LikeLike

Yes, I’ve intentionally not discussed tactiles because I wanted to establish principles first. I have some photos of Dutch systems for this. For me the question is just as you raise it… what can be done (in the UK environment) which does not undermine point A1 – the clarity that this is footway (because undermining this would increase risks to everyone, not least someone who needs the tactile paving).

LikeLike

No need to use a third material – in Denmark both cycle paths and carriageways are made from black asphalt, yet it’s clear that cycle tracks are continuous when the curb along them is continuous. The same should apply to footways.

LikeLike

I think we need additional clarity in the UK. Danish drivers are required to look for bikes and people crossing a side road. Here in the UK things work very differently.

LikeLike

Part A, footnote 4: you can omit the ramp at the property-side of the footway, but please do keep the ramp at the streetside. Keep the footway level, don’t make it dip down to meet the street at any/every driveway or garage entry.

B point 8: parking bays along the main road should end far enough from the corner that an approaching driver on the main street has a clear view of anyone on the continuous footway who might be approaching the crossing point, going in the opposite or, more critically, in the same direction.

If parking on the main road is not in bays but along the curb/kerb, a pavement bulb-out near the crossing, to the width of a parked car, can achieve the same result.

I disagree with point C5, but only in one direction. Bending the cycleway away from the main road so the driver from the main road, turning into the side road, meets the cycleway at close to a right angle, increases safety a lot.

The turning car can wait on the raised area between the ramp and the cycleway to let cyclists and pedestrians pass, before continuing into the side road.

If there is parking on the main road, the corner bulb-out together with a small curve-out in the cyclepath (and the footway, if necessary) can create enough room for this.

Examples: 1) If there’s a grass strip and/or row of trees between cycleway and footway, the grass ends before the crossing, and the cycleway bends out from the main road into the line of the greenery for the crossing. A sight-impaired pedestrian following the grass edge will notice the grass edge being replaced with the low forgiving curb/kerb to the cycleway before the crossing, which helps to signalise the approach of the crossing.

2) If the cycleway and footway run along the front gardens of the houses on the main street, those gardens stop before the crossing, allowing room to bend out both the cycleway and the footway at the crossing. This bend-out also helps to signal the approach of the crossing for a sight-impaired pedestrian who knows there’s a crossing somewhere around there.

These bendouts should be gentle curves, starting well before the crossing of the road itself.

But I agree: Do NOT bend the cycleway towards the main road, outside the protection of the ramp!

To translate this into your example:

In D2, allowing the cycleway to gently bend out a little would maintain the width of the footway (instead of increasing by nearly the width of the angled corners, in your example), and create both a right-angle view of approaching cyclists and enough space on the bulb-out for one car to wait before crossing the continuous cycleway+footway or entering the main street.

You might put the ramp up from the side street at the start of the angled corner, instead of slightly into it, to give yourself more room to play with the bend-out, but where you’ve put it increases the sightlines so is probably safer.

D3 works only if sightlines are long (because there really is nothing parked or stopped on the double yellow line) and speeds on the main road are not too fast, and if cyclists remain wary of cars paralleling or overtaking them then suddenly turning into the side street. It would be better to use this only where the side street is one-way and exits onto the main street, not where the side street can be entered from the main street.

D4 needs tweaking, e.g. the ramps need to follow the kerbline of the main road, and the entry lane for the side road needs to be narrowed and parking pulled back from that corner, but when all streets and footways are narrow (like in some historic city centers) a narrow footway by itself shouldn’t make it impossible to use a continuing footway design.

As is, it looks too much like the ‘side road entry treatment’ you refer to in the later picture from London.

As you said and linked, something a bit like D7 (a raised plateau but without the cyclelanes, and usually not including the footways – those generally stay separate and are not continuous) is commonly used at crossings between small, traffic-calmed, residential streets with 30 kph (18-20 mph) limits in the Netherlands. It forces all cars to take it slowly, and makes everybody give way to all traffic from the right (including cyclists, mobility scooters, pedestrians etc.), instead of giving one road (the level one) priority over another (the one with the ramps).

For this situation, it works well, but not for a crossing with a main road or on faster roads. So do tweak it but don’t exclude the idea of an intersection plateau for the car lanes completely from your design guides, but do limit its use to the appropriate circumstance.

LikeLike

Thanks Hanneke (as always). Some substantial comments there which I’ll need to read later!

LikeLike

I’m not visually impaired so my input on this should be superseded by anyone who knows what they’re talking about.

I’ve occasionally seen minor demarcation lines in a pedestrianised area marked by a row of metal studs inset into the surface.

There is no level difference for people to trip over, but they do make a different sound when tapped with a cane.

The ones I saw were used to mark the lines of an historic fortress in a modern plaza, and in a pedestrianized shopping street to mark a ‘through lane’ (together with a flush-set black kerbline and different red brick paving patterns) in the middle, where cyclists and faster walkers and faster-going mobility scooters tended to stay, from the same-level slow-moving windowshopping ‘wide sidewalk’ areas on both sides.

If English visually impaired pedestrians remain worried about the idea of continuous pavements, would putting a line of those studs flush into the pavement on both sides, marking the ‘through way’ for those vehicles entering or exiting the side road, give them enough of a signal so they know what they’re crossing?

The problem here is, that it is a continuous *footway*, not a road crossing. The cars need to wait, and the pedestrians need to walk across without stopping for the cars, to avoid introducing ambiguity and doubt.

If you mark it too well as something other than “this is my footway, I have right of way here” for the visually impaired, they may treat it like a road crossing and start to wait until the cars are gone. That introduces ambiguity, making it more likely that a car will try to cross while there are pedestrians waiting on the footway.

If that pattern sets in, all pedestrians become less safe on the footway.

For that reason, marking the continuous footway crossing point with tactile pavers (like a regular crossing) does not look like a good idea to me, as that is practically guaranteed to elicit that behaviour.

The metal studs might give a small notice of location, without eliciting the same behaviour. And if one misses them while tapping ahead, no harm done, as after all it is just a continuation of the same footway.

Does that make sense to anyone with experience walking with a white cane?

LikeLike

Our problem in the UK is that most (arguably all, to some extent) of the continuous footway so far added to our streets fails to be unambiguously footway (my condition A1) – usually also failing in many other respects (particularly by missing the ramps out). It ends up as a variant of ‘shared space’ design, and people wrongly assume that the two are related ideas/designs. This means that so far conversations in the UK about continuous footway and visual impairment are driven by people’s experience of the bad examples, and their difficulties with ‘shared space’.

To be fair, Glasgow has some pretty decent examples of continuous footway on some very tiny lanes (as detailed in ‘Design Details 1’) which are relatively close to meeting this standard (primarily due to the lanes being so narrow, rather than anything else).

LikeLike

This treatment might be called a D5, confused messages, but is seen as a big improvement for cyclists, who previously had to dismount to cross side streets, even if there was a marked foot crossing. https://goo.gl/maps/iBeEZLXE3qqkuUoQ8

LikeLike

That may or may not work, but is well outside of what the checklist covers. There’s no pretence that this is footway. One reason for writing the checklist is because lots of designs are being called continuous footway (or continuous pavement) and I’d like to reclaim the term so we can use it for what it was invented to describe.

LikeLike

Hello Robert, thanks for a great article. The tactile question is key though. I designed a pedestrian priority shared space project in Chester which has won a number of awards and I think could inform how tactile paving is used at side road crossings https://streetspirit.design/gallery

I located the tactile paving as far from the driver’s eye line as possible so they did not perceive it as the edge of a carriageway. In a similar way on a continuous footway, I’d locate the tactile , paving across the footway, prior to the end of the building line such that the blind/partially sighted are alerted they are entering a possible area of conflict, and drivers do not see the tactile paving, but only see the continuous footway.

LikeLike

Hi David. Thanks. Yes, definitely a key issue, but I also want to ensure we stay really clear that continuous footway (done properly) is completely different from ‘shared space’. There’s been some discussion on using guideline style tactiles (along the space not across it) as a way to add to the visual continuity. Colour is also key.

LikeLike

Some excellent discussion here. I agree with much of your analysis above, and only want to add a question about the purpose of the non-continuous footway treatment that you show in the photo above. As your conditions (for cont footways) require only *one-way* vehicular movement across the footway, then what do we do where two-way vehicle movement needs to be achieved? The raised table design shown has a role here, and has the significant advantage for pedestrians on the footway because it eliminates kerb level changes. That’s a plus for anyone with a scooter, wheelchair, balance bike etc.

LikeLike

Hi Caroline. A number of people have asked about that. I’ve not specified one way as the only solution, just that the space shouldn’t accommodate simultaneous two way movement. I think that in the UK context opening this up to two way movement crosses a line I think we should avoid… and that being specific that it must be too narrow for two simultaneous movements naturally also sets a limit on where a continuous footway can be used (if that won’t work because of volume of traffic then it can’t be a continuous footway for the same reason). Back to the zebra crossing analogy, this about ensuring that a new design is done really well, not compromised. Dutch designs in NL can be more compromised because people are used to them. Here we need to only do really good designs at this stage – until people driving know how to behave.

LikeLike

The solution, if the side road is two-way, is to narrow it (starting slightly before) at the crossing of the continuous footway, so the cars from both directions need to take turns.

And especially in that case it’s very important that the minor road is filtered at some point, so it’s only used for access to the adjoining properties. That limits the number of cars that might want to cross the pavement there, so you don’t get alternating queues.

Filtering out through traffic from the minor/residential road, if it’s presently used by more than a low number of cars, is important anywhere you want to use this continuous pavement construction, to avoid a queue building up*, but with an integrated pinchpoint it’s extra important.

* Sometimes, building up a queue can be the point, as discouragement for using a car for the short school run distance for instance.

Mind you, from what I’ve seen, according to Dutch ideas the ‘pinchpoint’ at the footway should be about one and a half cars wide if possible, so a cyclist entering or leaving the side road doesn’t get squeezed by the car if they try to cross the footway simultaneously; but they’ll have to wait behind a large HGV because those are wider and fill the whole width of the pinchpoint, as the danger of moving parallel to a HGV or bus would be greater.

As the car is going very slowly (at ‘walking pace’ which is less than 10 mph, =<15 kmh), crossing the footway, a cyclist can move parallel with it (from or onto the continuous cycleway) at the same time without being endangered by the relatively close proximity.

I'm not sure that would be quite as safe with British drivers unused to looking out for cyclists, especially if the cycleway is not bidirectional so the cyclist might be crossing the street too.

LikeLike

Yes. Exactly.

LikeLike

Great article, but your checklist might be too strict. For example, is this a “fail”, because this allows two-way car traffic? https://www.google.pl/maps/@53.0013014,6.5558809,3a,59y,289.4h,77.5t/data=!3m6!1e1!3m4!1skLU7yBM15T0K9mgJP7iDPg!2e0!7i13312!8i6656?dcr=0

Also, in the Netherlands the cycle track is not always straight with “continuous footway” design – just usually there is no space to make proper bends.

LikeLike

Thanks. Yes I think that the Streetview example you give, used in the UK, should fail the checklist. We have a very different starting point as regards driver behaviour and attitude, and also we should be building in accessibility concerns (safety for a wider range of people) from the very beginning.

LikeLike

Someone asked how the Dutch keep the look of the continuous footway the same, while the weight it must bear at the crossing point is much higher than on an ordinary footway only used by pedestrians.

The answer is in part the much stronger foundation, but also the versatility and adaptability of the concrete paving tiles and paving bricks used in the Netherlands.

The top layer of 12 inch square (30x30cm) concrete tiles used for footways all over the Netherlands are available in thicknesses of 4 cm, 4,5 cm, 5 cm (=2 inches), 6 cm, 7 cm and 8 cm, depending on the weight they need to bear. 4,5 cm appears to be most used on footways, while 6 cm is enough for ordinary car parking bays; the heaviest ones would be used for those areas where HGVs can come across them, like in continuous foot- & cycleways on an industrial estate.

For example, one online shop’s list: https://www.bestratingsmarkt.com/c-1556145/betontegels-30×30/

These all look the same from the top, their walking surface is identical (the choice to use a bevelled border or not is the only difference, not dependent on thickness); they are just thicker underneath.

To demonstrate their flexibility, here’s a big concrete producer’s for-sale list, with examples of all the colours they come in (standaard = the seven solid-coloured standard concrete ones, the others have more fancy top layers for special areas, which last less well if traffic uses them, and cost more):

https://www.struykverwoinfra.nl/productselector/machinaal-straten/tegels/trottoirtegels-30×30/tegels-30×30.html

Looking around on their site, you’ll also find the half-stone and bishop’s mitre stones used for edging when laying different patterns, as well as variations used for parking (6 cm thick, black, with a cross-hatched surface or embedded number), permeable parking surfaces, drainage, different curbs/kerbs, standard tiles with hollows for playing marbles, or with embedded texts like ‘doctor’, ‘no parking’, ‘loading zone’ or ‘fire access’, etcetera.

I’ve seen older ones, when pavements are dug up, that have a wavy undersurface: the top 4 cm is the same minimum thickness, but the surface below undulates to resist horizontal displacement. I can’t find those on any new for sale lists on the internet at the moment, so maybe they worked less well than just making the whole slab thicker.

The only ones that don’t have a solid undersurface I can find new for sale now are the ones on little feet, for use on roof terraces, so the water can run off underneath: https://www.nusierbestrating.nl/beton-bestrating/betontegels/betontegels-30×30/excluton-nokkentegel-30x30x4-5cm-grijs-groep – those are not meant for use by anything but foot traffic.

LikeLike

Hanneke – thank you as always. It’s invaluable having the information you provide on here.

LikeLike

Hello Hanneke,

Thank you for the information. This was the question I was planning to raise with Robert before I read your post.

If we look at Robert’s image D1, he has used the same area of paving throughout the footway, both on places with and without motor traffic. I’d assume this is because Robert wanted to focus on visual design in this blog and material specification is a whole other discussion.

However, in the UK not only do our continuous footways fail due to the visuals and lack of ramp. But I think a further issue is that the footway paving specification (possibly from a landscape architect) does not consider the visual issues if continuous footways are considered in the design. So we try and use smaller blocks at the continuous footway, but really we should be specifying materials for the whole footway, with considertion that stronger block version will look visually the same as the rest of the footway.

We have an issue in Glasgow where the smaller and larger blocks are visually similar, but the increased %area of mortar on the contiuous footway (due to the smaller block size) creates a visual differentiation with the rest of the footway.

I run the Transport Engineering stream for civil engineers at Glasgow Uni (where Robert’s ideas are a big part of the design components of the course), and am thinking of introducing material testing labs where we explore these issues (while smashing up paving).

Cheers,

Ali

LikeLike