I want my street to be like this…

Reclaiming residential streets, Dutch street design, and why this REALLY REALLY matters.

This might be the most important blog post I write on urban design – but it’s also been one of the most difficult. I want to demonstrate how to look at a quiet Dutch residential street, and to see what isn’t there – and to be amazed by that. Obviously that’s not an easy thing to do.

Look at this video. It’s quite a nice street isn’t it? Nice, but I don’t expect many people to be amazed by it. I’m going to try to change that. Perhaps you’re trying to encourage people to cycle in your city. You might look at this street and say ‘so what?’ – and go looking for one of my articles on segregated infrastructure. But if you do that you’re going to miss out on something really big and really important about what makes Dutch cities what they are, and what might make our cities substantially nicer to live in.

I’d like people to look at streets like this and to say “wow that’s amazing”.

So get yourself a cup of coffee and a biscuit, or glass of wine if you prefer, and let’s get started. Trust me – it’s worth it. (Although if you really have to have nothing more than 3 minute version of the article then jump below to the main animation and just watch that.)

I’m going to write about the UK quite a bit in this article, but I hope it will be just as useful to readers from elsewhere. My objective is to explain why the Dutch infrastructure is amazing – and to support a way of seeing and understanding Dutch design – and it’s easiest to do this by making comparisons to another country.

The “what’s different?” challenge

Take a look at these ten photos. Five are of UK (Edinburgh) residential streets, and five are of Dutch (Amsterdam) residential streets. I’m sure that most people can immediately tell which are Dutch and which are from the UK (this should be very easy for UK readers, but perhaps a little harder for international readers). How is it possible to tell?

Ignore the differences in building design and ignore what the streets have in common.

Focus on what’s different in the street layout.

Maybe also take a look on Google Streetview. Drop in on the Dutch cities at some random location – perhaps choose somewhere with a reputation for being particularly good for cycling. You’ll probably land on a street which looks like one of the Dutch ones above. The Dutch designs I’m showing here aren’t unusual. In general terms this is roughly what most streets in Dutch cities look like (outside of industrial areas).

What is it which makes them feel Dutch? What’s different to how the UK (or your country) works in comparison?

Throughout this article I’m going to encourage you to refer to Google Streetview. Try to do this for real – I’m going to make big claims. Don’t just trust me – you can check this out yourself – and agree or argue that I’m wrong if you like…. You WILL be able to find locations where what I say isn’t true – but how common are these? Clearly I’m generalising a lot in this article, so if you think I’m wrong then how wrong am I? Is it just about fine detail? Am I right in the overall thrust of my argument? Or not? Do comment below.

Now – lets make the challenge easier. I’ve taken out all the distractions and created an animation (below) to help.

The animation switches between typical Dutch and typical UK designs.

- I’ve used exactly the same building layout, the same distances between buildings, and the same overall street pattern, and even the same lighting on the ‘Dutch’ and ‘UK’ models.

- I’ve missed out some details which are common to both countries, and which I feel to be less important… like street lighting.

- The buildings look like some kind of apartment, but they could just as well be separate houses – I aimed for something simple to model – ignore them and concentrate on what’s between them.

I think that some of the differences we see here are really dramatic. I hope you do too.

It would be easy to assume the Dutch streets feel different, just because they are Dutch. Or we may assume that they feel different just because fewer people are wanting to drive. Or we may think that what makes the difference is the number of people on bikes.

I see this the other way around.

It’s the urban design – the way that the street is designed – which makes them feel different, and the people cycling, walking, and living there… sitting in the street, standing talking… are doing that because the design has facilitated it.

And – incredibly importantly – there are fewer people driving in these streets because that’s how they have been designed, not because people don’t want to drive through them. If we put UK street designs in the Dutch cities then they would feel like, and operate like, UK cities. Dutch cities work the way they do because of the way their streets are designed – and UK cities work the way they do because of the way their streets are designed.

I’ll say more about this later.

Top level differences

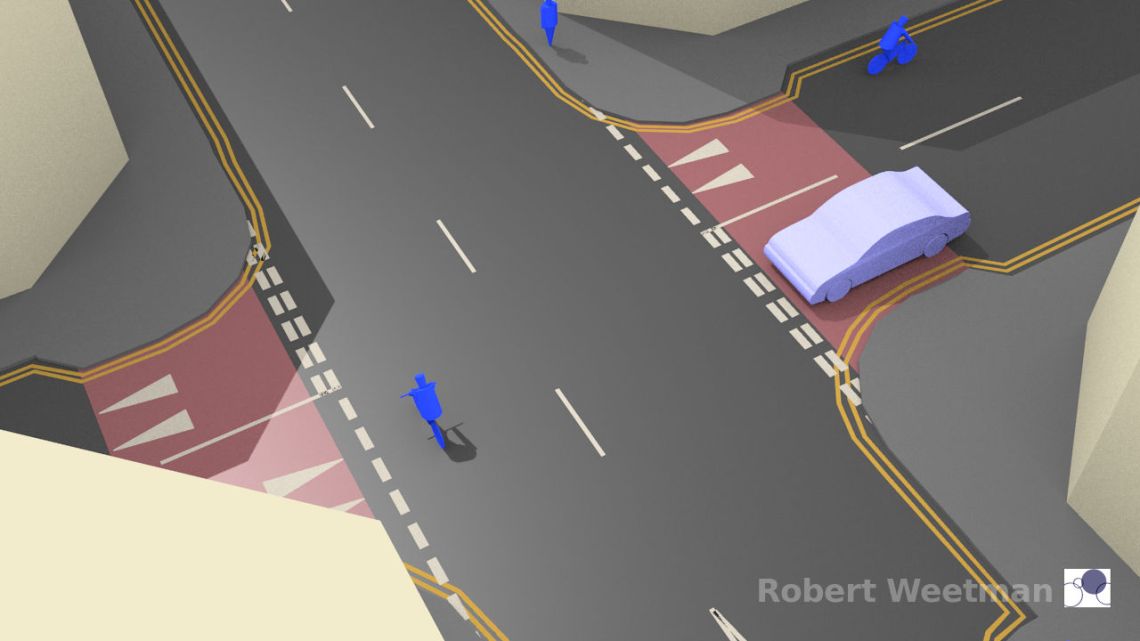

Before we get into detail (answering the “what’s different?” question in depth), let’s take a moment to think about what ‘top level’ differences can be seen in the animation. This second (much shorter) animation illustrates one of the biggest:

Overall, what I see in Dutch design is a street-space from which a minimum and very limited area for driving on is cut out. I’ll use the UK word ‘carriageway’ for this part of the street. Because this space for driving on – the carriageway – is so tightly controlled it tightly controls speed (not always enough, but much more than UK street design). The general assumption is that the street is for multiple purposes (it’s quite common to find play areas for children also cut out of the street-space).

(Click/tap for larger images – these are from two different sections of the model)

Below I’ve taken some of the images of Dutch streets that I used earlier, and I’ve drawn red lines along the edges of the carriageway. The red lines show the edges of the bit of the street that looks like it’s designed for driving on.

(Tap/click for larger images)

Overall – in contrast – what I see in UK street design is the assumption that the primary purpose of the street is the movement of traffic.

In contrast to the Dutch approach (with minimum space for driving), the need for space for walking is accommodated by providing the minimum footway. If there are individual locations where this minimum space is inadequate, for example at key locations where it is impossible to cross a road, some secondary features may be provided to improve things a little. And (again unlike the Dutch approach) any space not currently used for a parked vehicle becomes available for driving in. Parking is restricted only to allow for the movement of motor vehicles.

Below are some of the images of UK streets I used earlier. The red lines indicate the edges of the carriageway – the edges of the bit of the street which appears to be for driving on.

Learning point: Dutch residential local-access streets define a much narrower carriageway than is used on UK residential streets. They provide only what is needed for one-way vehicle movement and nothing more. Parking is off the carriageway, and vehicle speeds are severely controlled. The effects of this design are not only physical, but also visual (and the streets feel very different too).

All the other differences

What other differences are there? What other details can we see which make a difference? Well be assured this isn’t a dry technical exercise… some of the other differences are also dramatic.

One-way versus two-way

Dutch residential local access streets carry one-way traffic if possible.

UK residential streets carry two-way traffic if possible – this image is from exactly the same position in the UK model as the image from the Dutch model above.

In Dutch residential streets it is normal for one-way restrictions to apply to motorised vehicles only.

I didn’t draw the relevant signs on my animation – but I’ve assumed they are there (so the person cycling towards us here is doing so legally). Most ‘one-way’ and ‘no-entry’ signs have an ‘except bicycles’ sign, exempting people cycling from the rule:

Some might assume this would be unsafe, but it is so normal, and one-way streets are so common, that anyone who drives expects to see people cycling the other way.

This means that residential areas are permeable on a bicycle, in all directions, but are very difficult to drive through using a motor vehicle.

Learning point: Dutch one-way streets are an essential tool in prioritising cycling over motor traffic.

On UK residential streets it is usual for one-way restrictions to apply to everybody, even if they put people on bicycles at a major disadvantage.

There’s a common belief in the UK, which is that one-way streets are ‘bad’ because (it is argued) vehicles are driven faster on them. It is also said that one-way streets will mean people visiting a location might need to travel a bit further, with the result that any one location will see more traffic. I hope the images I’m showing here demonstrate how damaging these myths are.

Clearly if we change a two-way street, like those I picture in the UK model, to be one-way – without any other changes – then vehicles might be driven faster on the wide space. But do the one-way streets I’ve modelled here look like places where vehicles will be driven faster? My experience of the Dutch streets is so much the opposite.

Learning point: One-way streets, appropriately designed, can significantly cut traffic speeds and volumes.

I describe this situation in simple terms of preference for one-way streets. In truth on wider residential roads – perhaps further from a city centre, or where there is a lowered pressure for parking and already plenty of footway space – Dutch design is quite happy with two-way streets. Like all the principles discussed here, variation from this starting point can be seen if you look at Streetview images – but I hope what you’ll see is the application of the set of principles, but with an appropriate response to the individual location.

Junction priority

The two images below are animated, changing between Dutch and UK designs.

Dutch residential street junctions have no marked priorities. Their Dutch default ‘yield to the right’ rule applies, meaning everyone may have to give-way. They are very careful to alter the shape of junctions like this to ensure that nobody assumes priority (the bend in the street in the design I show makes it clear that this is a three way junction).

The result is that each junction in a residential area acts as a traffic calming feature.

Generally (given reduced levels of traffic) people cycling here don’t need to slow down at all from the steady Dutch cycling speed.

UK residential street junctions almost always have marked priorities. The aim is to ensure that nobody is in any doubt that vehicles on one of the roads can maintain speed, while vehicles emerging from the secondary road have to wait.

Learning point: Appropriately designed junctions, with no priority markings, act as traffic calming.

There are many other important design features used at Dutch residential local-access street junctions.

The junctions are designed, like the streets, by providing just the minimum space needed for vehicle movement. Traffic has to negotiate junction space slowly because the space is tight. There are often hard features, including bollards, forcing slow speeds.

Parking is restricted to increase the space for footway, and to improve sight lines so that people on foot and cycling are safer.

UK residential junctions lack these features. Footways tend to remain at the edge of the street, perhaps with a ‘build out’ on occasion, or some minimal change to street colour or surface level. Most of the street space is for vehicle movement – and if parking is restricted it is to facilitate this.

Learning point: Junctions combining the narrow Dutch carriageway, with no priority markings, leave lots of public space and wide open areas for city life to thrive.

Some more sceptical people might complain that I’ve drawn standard UK junctions here, not improved versions as are described in the modern policies of some cities. But how much difference do you think that these ‘improved’ junctions make – when you compare them to the Dutch designs?

Are you really sure that those gentle speed humps at the road ends make any difference? They might be painted red (or the paint may have worn off). They might not be speed humps but cobbles or some other feature. It might not be possible to drive over them at 40mph (but 35mph is fine). There might (as above) be some small ‘build out’ features to narrow the gap a little, or to reduce the radius of the curve of the kerbs. But really how much difference is this really making? Some perhaps? Or is this just ‘window dressing’ in comparison to the Dutch design?

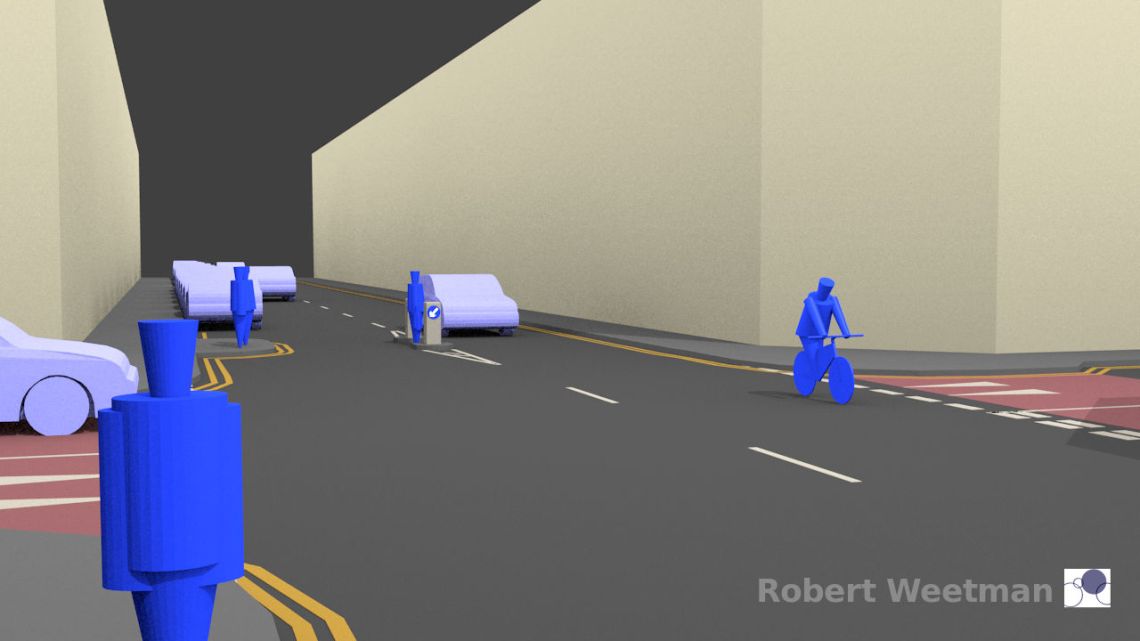

And maybe there could be a minor build-out on the bigger road too? You can see there are two people waiting on a build-out in the background of this image. It’s a little bit easier to cross here than it was before – but this design shares almost nothing of the Dutch streetscape. The ‘build-out’ is clearly a build-out not a normal section of footway – it’s a temporary refuge from traffic, not somewhere you’d stand for a conversation. Compare that to the Dutch design. The overall feel of the street is basically unchanged by this build-out. Is it better than nothing? Perhaps. Is is ‘good’? Not in comparison to the standard Dutch approach.

Carriageway surface

The surface of Dutch residential local access streets is very often of street bricks. This is a very important signal to people driving on these streets that they are not on a main thoroughfare. In general this is consistent across the whole country.

The colour and design of this surface creates a warmer streetscape compared to the UK use of black/grey tarmac/bitmac. Sometimes the slightly uneven nature of these bricks, on older streets, can also be significant in creating a message about how the street should be driven on. I’ve drawn these street bricks on my animation, which is a key reason for the Dutch model looking warmer and sunnier (despite me using the same lighting in both models).

Note that Dutch street bricks are nothing like old UK cobblestones. These are a modern surfacing material, and can provide a smooth surface. They also provide a surface which is permeable to water (look up ‘water sensitive urban design’ to understand why this is now seen as so hugely important internationally) – I’m reliably informed that it has been being taught, for at least 20 years in the Netherlands, that this is a good reason to use street bricks.

Here are more photos of the real thing:

Street bricks aren’t universal, but they are extremely common.

The surface of UK residential streets is almost always built from the same material as the surface of any main street/road. The tarmac may be more worn, but when the street is resurfaced it is brought up to the same standard (in general terms) as any main thoroughfare. There are very few national distinguishing features indicating a difference between residential streets and main thoroughfares. Often the speed limit doesn’t even change.

Parking is handled completely differently

As already alluded to above, and shown in many of the images, parking in Dutch streets usually works completely differently in comparison to the UK. We already discussed above the way that parking feels like it is off the carriageway. There is usually a different surface material, or at the very least a change in the pattern of the street bricks. There’s commonly a broken dividing white line along the carriageway edge – helping to mark the narrow width of the carriageway even when there are empty parking spaces.

But what’s also worth noticing is that it is assumed that parking is not allowed unless a space is provided for it. That means that there are no yellow lines along road edges marking where parking is prohibited.

Let me emphasise that last point, because not many people notice this…. There are no yellow lines marked along the edges of Dutch streets for controlling parking.

UK parking is on the carriageway. There is no difference in surface material. It is assumed that parking is allowed unless it’s marked as not being allowed. UK cities have thousands and thousands of miles of yellow line painted along the edges of their streets.

Can you imagine taking our system to Dutch cites and trying to tell them that it’s a good one? Instead of marking the places to park, they’d have to paint yellow lines along the edges of all their lovely homely streets… I don’t think they’d buy the idea.

If you want the full story about Dutch parking rules, rather than this simplified version, then take a look at the links and descriptions provided by ‘hanneke28’ in the comments at the end of the article.

Learning point: Dutch streets don’t have yellow lines drawn along them to control parking. The system (in busier locations) is to mark where it is allowed, not where it is not allowed.

Trees

Dutch residential streets often/regularly have on-street trees. Often there aren’t only a few trees, but many.

Some UK residential streets do have street trees, and there are cities where these are more common, but they certainly aren’t a normal feature when you look at the UK as a whole. They work more like a luxury feature. In places with more money, or wider streets, they are sometimes included. If the streets are narrower, or money tighter, or the perceived need to move motor vehicles is greater, they are missing.

Who ‘owns’ the space

Dutch residential street space often feels like an extension of the nearby houses. It’s clear that the local people – in many places – feel that this is ‘their’ space. There is often greenery looked after by the residents (and there are often weeds, moss, grass growing in cracks too). There may be benches belonging to the residents. Their bicycles are left there. There are signs of human life.

UK residential street space generally feels sterile, and is clearly the territory of the local authority (council etc). It is clear that local people do not regard this space as ‘theirs’. Weed-killer may be used here to ensure that no weeds grow. It is seems that benches or plants belonging to a resident would probably be removed (even if there was space for them).

This is an image from the exact same spot in my UK model as is shown in the Dutch version above.

Now clearly my model is simplified – in many ways. The bicycles in the Dutch model are all in a neat row. Because I’m not modelling the houses the UK model loses any softening effect that might exist because of private gardens. You might claim that this makes the comparison unfair – but I don’t think it does. After all, I’m wanting to emphasise how the street works – not the overall amount of greenery present in an area. How the street works changes who feels safe on it, how people travel, what people think it’s for. There are some nice UK streets – but what I almost always see is the domination of the strip of sterile tarmac which lies between one private space and another.

If you stand on the footway of many Dutch residential streets and ask “who loves this space?” people will point to the local residences. If you stand on the footway of most UK residential streets and ask the same question, people will think you are strange (I’ve done this by the way – and it was only when I explained with one of the images I show below that people understood why I was asking this).

How many UK city streets look like this? I’m sure we can find some, but this in completely normal in Dutch cities.

Not all streets look exactly like this of course – these particular images are all in central Amsterdam, and I’ve chosen them because they match what’s in my model. But go searching using Google Streetview and you will find that is very normal that a street feels like there is a merging of private and public space. This is absolutely not my experience in the UK.

Area-wide nature

More sceptical people might look at my animation and complain that this street in the UK model (below) has been drawn as if it’s more important – as if it is required to carry more traffic – than the comparable street in the Dutch model. They might assume that good design must allow for this flow to continue.

Such people might argue that the comparison is unfair because in the Dutch model I’ve shown a street clearly designed to carry less traffic.

In one way they would be correct. Quite clearly the Dutch street, at the same location in the model, couldn’t carry the amounts of traffic shown on the UK model.

But that’s the point of course. The Dutch system takes streets which in the UK would be seen as key routes (with a supplementary residential function) and decides that they are residential local access streets – not urban through streets. They are then designed so that cannot any longer carry large volumes of motor traffic.

In the UK one of the least understood elements of Dutch design is the way that their ‘Sustainable Safety’ policy works in achieving this end (perhaps a better translation is ‘systemic safety’ or ‘systematic safety’). I’m not going to describe it in detail here – but here’s something everyone should know…

The Dutch streets in locations like this are either classified as urban through streets or residential local access streets. The Dutch words are gebiedsontsluitingswegen and erftoegangswegen (which I’m not translating literally). You may notice that I’ve tried to use these classifications throughout this article because I want to emphasise how important they are.

For an explanation about why I’m using non-standard and non-literal translations of ‘gebiedsontsluitingswegen’ and ‘erftoegangswegen’ please see the note in the appendix at the end of the article.

This isn’t just a classification for the sake of classification. That’s what often happens in the UK – a street is classified in one of many different (probably local) ways, but that classification is really just a description of the way the street currently operates. In the Netherlands this classification really matters because once it’s been decided which category a street belongs to its design is changed (at some point) to match what’s required for a street in that category. For the kinds of street we’re looking at here there are only really two classifications available – urban through street, or local-access street. That makes the system beautifully clear – except in exceptional circumstances the street has to be one thing or the other – and this is the same across the whole country.

Here (in our model) we have a street which might have been classified as an urban through street – but instead a decision has been taken that it’s to be a local access street. The reason that it now looks so different is because once this was decided it has been re-designed to prevent through traffic.

If, instead, it been decided that it was to be an urban through street, the design would also have been changed. Then the safety of people cycling and on foot (etc) would take precedence (generally speaking) over the needs of people to park. Some kind of segregated cycling facility would be provided, even if parking had to be removed to fit it in.

Imagine if the choice that was given in the UK to local people – about their streets – was between 1) a very quiet one-way street with plenty of parking, but no through traffic, and 2) as street where parking was limited because cycling takes priority. Imagine if it was national policy that streets had to be one of the other.

Learning point: The Dutch Sustainable (Systematic) Safety policy is about infrastructure design, and over time its influence has been profound.

Dutch residential local access streets are in large blocks, with urban through streets around the edges of these areas. The transition between urban through street and residential local access street, is obvious – with people needing to drive over the footway to enter the area, and the streetscape changing radically and immediately upon doing so.

There is a great deal more about ‘continuous footway’ – where the footway is continued across the end of a residential local-access street – in this previous article (‘Design Details 1’).

There is a change in speed limit when entering an area of residential local access streets over this continuous footway. The continuous footway acts as much as a gateway feature as it does a support for walking and cycling on the urban through street. It is obvious that the speed limit in these areas is lower (although driving faster would be difficult anyway). The one-way systems in the residential local access streets almost always make it very difficult or impossible to drive through an area as part of an ongoing journey. Those driving in a residential area are only normally going to be accessing or leaving one of the properties in that area.

In comparison it is unusual for there to be any features in the UK which clearly distinguish local residential streets from any other roads and streets. There is absolutely no transition marked here (in the image below, from the equivalent point in the UK model)- the street ahead is just another UK street.

There may or may not be a change in speed limit, but this is generally only indicated by signs, and driving faster is common and easy to do. There may be traffic calming features, but these look no different to traffic calming anywhere else. Where decisions have been taken to limit through traffic it is often on a street by street basis.

For a few words on my choice of language around ‘sustainable’ or systemic or systematic safety please refer to the explanation at the foot of this article.

But parking is equal

Last in this list – here is what is not different.

There are generally, in Dutch city streets, just as many cars parked as there are in UK city streets (and certainly in the Dutch streets which look like those I’ve modelled).

Roughly speaking, depending on exactly how you count, there are the same number of parked cars in both my models. The cars are distributed a little differently, but actually Dutch design leaves plenty of space for parking (and if anything can be criticised for making residential streets into car-storage areas).

Why this all matters

I don’t hear people talking about these things. I speak to lots of people about Dutch cities. I follow lots of Twitter feeds which describe Dutch design. I hear lots of debates about how to find a way forward for supporting people to cycle and walk in our UK/international cities and towns. I rarely hear people talking about how Dutch residential local-access streets are designed. I rarely hear people talking about the Dutch Sustainable (or systematic) Safety policy/system.

People tend to be drawn to images of segregated infrastructure – lovely Dutch bicycle tracks, and beautiful sweeping Dutch bridges for walking and cycling over. People even point to the Eindhoven ‘hovenring’ as something we should aspire to. The hovenring is just a glorified bridge over a motorway-like road. It’s a very impressive piece of engineering, and it’s a sign that money is spent on infrastructure for cycling, but it’s just a bridge.

Nice bridges, and beautiful cycle tracks are really important – yet I think that too few people stop to think to analyse properly…

What proportion of Dutch urban roads/streets have segregated cycleways?

Take a look on Streetview again. Look at the proper urban areas rather than any industrial estates. The proportion of Dutch streets in these areas which have cycleways of any kind is actually pretty small. Most Dutch city streets do not have segregated facilities for cycling BECAUSE they are residential local access streets and they are consequently good for cycling on already.

The re-designs I’ve shown here, in general terms, make these residential local access streets:

- good for living on;

- good for walking along;

- easy to cross;

- places where you might be able to sit in the sun;

- places you can speak at normal levels because there’s minimal traffic noise;

- places which feel a bit like an extension of the private space around them; and

- good to cycle on.

Learning point: Dutch cities and towns are good to cycle in, despite only having segregated infrastructure for cycling on main urban through-streets (and beside more major roads too).

Many UK schemes to increase cycling begin with trying to increase segregation on main streets, while ignoring the nearby residential streets. But the Dutch system works as a unified whole. They couldn’t do what they do for cycling on their main urban through streets without doing what they do on their residential local access streets. The Dutch segregated cycling tracks work BECAUSE of the design of the nearby residential streets. This is part of a unified design strategy.

In the UK changes to introduce segregation for cycling on main streets inevitably impact on parking and loading. This is particularly the case where parking and loading have previously been prioritised over the safety of people cycling.

And UK changes to introduce segregation for cycling often fail miserably due to design compromises when at side-roads. Huge and disastrous, or even dangerous compromises are made where maximum vehicle permeability is still being sought in the residential streets. Dutch continuous-footway (and cycleway) works as a design because it’s used in the way I describe above – it isn’t used to take cycle tracks or footway across major roads. If the road is a major road then that major road also gains segregated cycle tracks, and probably proper traffic signals or a roundabout will be provided at the junction. If it’s not a major road then it becomes a local-access street – as above.

In my view, changes to main streets to support cycling MUST be accompanied by changes to the nearby residential streets.

But this isn’t a scary thing – this might broaden the scale of the changes we need to discuss, but it’s a MUCH better way to work and has huge advantages as far as local people are concerned.

It means that overall parking levels can be maintained, even if parking is changed on a main through street. This may not be ‘good’ in environmental terms, but at least should reduce objections.

It means that segregated infrastructure can be built in such a way that it is no longer fatally compromised at side road crossings.

But most of all, if we work this way it means that the biggest effects of the overall changes in streetscape are to improve the quality of life of the local residents, with improvements to the safety of ‘cyclists’ (people cycling through the area) being only one part of a whole unified scheme.

Of course if we only do this in one area we might make ourselves unpopular – after all one person’s local area is another person’s through-route. But once we start to consider this as city-wide policy we should find that everyone living in a city has their own local area that they’d like to see improve.

I think that this is something worth striving for. How about you?

I want my local street to be like this:

Appendix – Sustainable/Systematic/Systemic Safety

Those in the know will notice (and some might object) that I’m not using the most literal/common translations of the Dutch words gebiedsontsluitingswegen and erftoegangswegen – and I’ve copied Professor Furth (as discussed here by ‘Bicycle Dutch’) in introducing the word ‘systematic’ but also I’m going further in using the word ‘systemic’ rather than ‘systematic’.

The Dutch Sustainable Safety approach is discussed very little in the UK – and I often think that people assume it to be some kind of behaviour/safety campaign rather than a policy directly influencing infrastructure design. In this article I only want to convey some of the most important features or effects of the approach – and indeed to highlight how important it is.

I’ve done my best to find appropriate phrases, which concentrate on conveying meaning rather than on being a full explanation of Systemic Safety (using ‘local-access street’ and ‘urban through street’ consistently above). I’m also adding this explanation to the bottom of the article so that curious people are clear that the words I’ve chosen aren’t standard ones.

Someone may be able to come up with better phrases than ‘urban through street’ and ‘local access street’ – and others might argue that more common translations are just fine – but this article isn’t an attempt to explain the whole Systemic Safety approach anyway. I think that clarity in this article is more important than sticking to traditional translations.

No phrases will be perfect, and those I’ve used here may not work in other countries. In the UK the word ‘street’ is used in the urban context (where people live or walk or shop), whereas ‘road’ is more general. Streets always also roads, but not all roads are streets. The word ‘distributor’ in the UK (often appearing in translations) is often associated with large multi-lane motorway-like roads – even though this is not its literal meaning. It’s probably used more literally elsewhere.

For the article above, and in an urban UK context, the key difference between these road types is the assumption that ‘gebiedsontsluitingswegen’ carry vehicles through an area, whereas ‘erftoegangswegen’ are designed to not allow for anything other than local traffic (discouraging through traffic). Many in the UK will find it difficult to believe that cities can work in this way – so I want to use phrases which make it as clear as possible that this is the Dutch approach.

And whether ‘systemic’ or ‘systematic’ is best… who knows. To my mind ‘sustainable safety’ simply doesn’t mean what we need it to mean in English. I suppose ‘systematic’ means something practised consistently and across a system in a focused way to achieve a goal. ‘Systemic’ on the other hand means something which is at the level of the system.

In the end it won’t matter, because the meaning of any phrase soon drifts once people start to adopt it – but for the moment I’m going to commit to the phrase “systemic safety” because I think that implies something at the level of the system – and reminds us that what we’re looking for is high level changes of principle, not just focused and systematic application of existing principle.

Our current system is fundamentally focused on the movement of vehicles at the expense of human safety and well-being (on the basis that ‘accidents are basically unavoidable). What I’m working for is a change to this system, so that the system is instead based on the idea that safety comes first, and that movement of vehicles should only be allowed if this isn’t destructive of human life and safety. That might sound idealistic, but it only mirrors what’s happened in the workplace in the UK and many other countries over the last hundred years or so.

Once upon a time if a worker died in your employment you might be able to argue that it was just an accident, a product of the worker’s carelessness perhaps, or just an unfortunate chance occurrence. Nowadays – at least in broad terms – if a worker dies in your employment the assumption is that you’ve been incompetent, or neglectful, and that this is true even if the worker made a mistake.

Please feel free to discuss this in the comments below. If someone can point to a good enough reason I may even update the words in the article.

For anyone curious to find out more, there’s a link below.

See also…

- Amsterdam vs Copenhagen (part 1) (basic cycle track anatomy)

- Amsterdam vs Copenhagen (part 2) (basic junction anatomy)

- Amsterdam vs Copenhagen (part 3) (what can we learn)

- What nobody told me (about Netherlands urban design)

- Design Details (1) – Continuous footway. Side-road crossings. Simplicity and clarity. Getting it right. Getting it wrong

- Read everything – New here? This is a suggested reading order.

External links…

- Sustainable or Systematic Safety by Mark Wagenbuur (Bicycle Dutch)

- Sustainable Safety by Paul James / Cycling Embassy of Great Britain

Comments…

As ever, I welcome your comments. If you disagree with something I say then let me know. If you can help me explain my points then please do so. And read the comments of others to see what they think too – there’s some in-depth knowledge already offered by others if you want to keep learning.

If you’re Dutch (or have detailed Dutch knowledge) you might disagree with some of the generalisations I make. You might know of streets that look nothing like those I picture. I do too – but I’m explaining principles here. If you think I’ve generalised too much or that there are details which I’ve glossed over then do say so.

If you landed here from a Twitter link on a mobile device you may need to press ‘Leave a comment’ below to see the comments on this article or you can reload the page to see them.

I think you’ve captured the essence of old town and city streets very well.

New neighborhoods where land is costly also often use this kind of pattern.

It’s really interesting to see this stuff I’ve always taken for granted through new eyes, because of your very clear explanations.

I’ve got one addition to your diagrams and explanations of local access streets.

In newer neighborhoods, and older but more spacious ones, sometimes another mechanism is used to create the same effect, instead of one-way streets. The streets there are sometimes (just) wide enough for two cars to pass each other, and not signed as one way; but rat-running and through traffic are eliminated by the way the circulation plan for the neighborhood is set up.

The whole neighborhood will have only two or three exit- and entry-points for cars, and at least double that for bicycles and pedestrians, with an urban through street running between the car junctions, usually on something of a loop. All the other local access streets, coming off the urban through street and connecting only to more local access streets or dead ends (at least for cars) are a bit of a maze that will always be slower than the urban through street, so making it very unlikely that anyone will go wandering around the houses instead of taking the urban through street if they want to get to an exit junction.

Each neighborhood urban through street then connects at the entry/exit junction to a larger city-wide network of town urban through streets between the neighborhoods (or maybe a local ‘ring road’), which will (almost) always be easier and faster than snaking through the neighborhood ‘through street loops’ from one neighborhood to the next. At peak times, a few cars from the next neighborhood might take ‘our’ neighborhood urban through street to get to the ring road, but no more than that – and as it’s a through street, it’s designed to handle that traffic.

For an example of this, you could look at Heerhugowaard on Google streetview [OSM map | Streetview]. It used to be a small village until 1960, then it started to grow fast. You can see the square blocks of each new neighborhood clearly on the map, on both sides of the old Middenweg (Middle road) – the most recent one, Stad van de Zon [ OSM map | Streetview ], is the same size but purposely tilted at a 45 degree angle and surrounded by a recreational lake.

You can see the age of the neighborhood from the street patterns inside the block – e.g. Edelstenenwijk (streets named after gemstones) has the typical seventies cauliflower pattern [ OSM map ], but the next neighborhood Butterhuizen (streets named after endangered animals) [ OSM map ] was built in the nineties and has a lot less dead ends and more loops. Both however have the same effect on car use: only people with destinations on those local access roads drive there.

In Butterhuizen, Reuzenpandasingel is the urban through street, connecting with the town ring road of Westtangent on one side, and to the urban through road grid via Middenweg to Amstel, which is part of the (now inner) ring road from the seventies, connecting the older neighborhoods it passes to the Westtangent, and is still being refurbished piecemeal.

Gibbon was set up extra-wide from the start as a future connection to the new ‘Stad van de Zon’ neighborhood, but all the other streets are either 1 car + parking narrow (e.g. Woestijnvaraan), and sometimes one-way (the service/access roads paralleling Reuzenpandasingel), or 2 cars wide (Steenuil, Harpij) but not conceivably part of any ratrunning shortcut except for bikes – Steenuil & Andesconder connects to Middenweg, but not for cars; there’s a bike path through Luipaardpark to Edelstenenwijk but no direct car connection, etc..

BicycleDutch showed a map with a retrofit of this idea (of limiting through routes so that each entry point connects to only a few exit points, thus making the rest of the local access roads inefficient for anything but destination traffic) onto an old town neighborhood in Utrecht in this blog from 2015: https://bicycledutch.wordpress.com/2015/12/15/how-to-prevent-rat-running/ and I’ve seen an example from an English bicycle blogger (maybe RantyHighwayman or HackneyCyclist?) on Twitter who made a map of an English seventies (?) neighborhood and how this could be put into practice there (including bicycle cut-throughs from dead ends to the next street).

As a lack of connectedness is seen as one of the indicators that long term a neighborhood might do less well economically, it is important to make sure that while you limit car access points, there are extra access points for bicycles and pedestrians, so the neighborhood stays lively and doesn’t become stagnant.

Not that that will *always* be a problem, many rich little neighborhoods have only a single car access point and remain very highly sought after, like this tiny maze in Heiloo: even without any facilities at all it’s very quiet to walk or bike through (and of course, bikes get 3-4 access points).

Sorry, that’s somewhat off-topic, but it clearly illustrates that lowering the volume and speed of traffic is much more important than any specific facility.

[several links to maps added in an edit by Robert]

LikeLike

Thanks hanneke28

As always you’ve given me more work to do – and I’m pleased. I’m going to need to spend some time working through those comments with Streetview and other maps. I might add some additional links to your comment too if that’s ok – to help people see what you’re talking about.

I hope what I manage to convey here is a way to understand the set of guiding principles which lie behind the Dutch way of doing things. Armed with these it’s very valuable to ask what designs are used when the general shape of an urban area is quite different – or where streets are of a substantially different width (wider streets with fewer junctions makes it harder to use the one-way approach). I’m aware myself of residential Dutch areas which feel different to those I’ve pictured – but I still feel the same guiding principles behind how these work.

In the UK we use the phrase ‘filtered permeability’ – which people usually think of as including the kinds of pedestrian/bicycle only ‘filters’ which you talk about. Mark Wagenbuur (Bicycle Dutch) and others have written well about the way this is done in the Netherlands, and it’s fairly easy for people here to understand this approach.

I’ve also seen places in the Netherlands where I think the approaches used elsewhere might be being forgotten – Almere Poort for example. I can see that as the place develops it may change, but it felt to me that the approach here was more in line with what would happen in the UK (and the results will be a car-dominated area I think).

LikeLike

Yes, I’ve seen David Hembrow comment on that as well, that some of the newer urban planners appear to have forgotten the lessons learned about improving bikeability and limiting the use of cars; or they’re not content to copy older established designs and want to put their own stamp on the urban environment, or they want to experiment with possible alternatives, but end up re-making old mistakes. They take biking everywhere so much for granted, they don’t realise it needs to be specifically designed for to keep happening. I didn’t either, until I started reading these English blogs about Dutch biking…

Almere was designed from the start, at the height of car dominance, as overflow housing for Amsterdam – people were meant to live in Almere and drive to work in and around Amsterdam. That mindset is still active there.

The examples I gave are not so much meant to convey a different feel, as that even with a different road profile (less narrow carriageway, no one-way signs) these neighborhoods with similar functions can have a similar feel, as long as the effect on vehicular traffic is the same. They’re both residential areas, with greenery in every street and play areas in walking distance, where cars stay in marked parking spots and there’s no through traffic, kids play outside, parents chat while three and four year olds can practise riding their bikes in the street in front of their house or on the pavement around the block, and elementary school kids can safely walk or bike to school, and cats can sometimes even nap in a sunny quiet street.

They do have all the extra’s you point out, like good pedestrian pavements free of parking cars, greenery and play areas. Not always much bicycle storage, as these newer houses will all have their own bike sheds in the garden (those have been mandatory for any new building since the eighties). That means you can only allow the wider carriageways if there’s room left over after all the people-space has been put in, and the carspace might be needed for example to allow for room to turn into perpendicular parking spots.

If land speculators have driven up the price per square meter, towns will often go for the narrower profile to keep the housing affordable – if not, a roomier profile can be used (with added greenery) that makes the neighborhood more attractive and still stays within market range for the houses. Viz the difference between the northern part of Butterhuizen (land bought by the town to be sold to the builders before speculators caught wind of the new developments), and the next-to-be-built neighborhoods to the east and south, where streets are more narrow, people have to park in their own front garden (as is noted in the sale or rental contracts), and there’s less room for public greenery. For instance, Rosa Spierplantsoen [ Streetview link ], just across the Middenweg from Butterhuizen and built shortly after, has a profile that looks much more like what you describe in this article, but its narrowness and the visually more dominant cars are a function of the higher square meter price (in this case due to land speculators, but the same is true for city centers), and don’t denote a different type of neighborhood.

If you want to add more map-links, or correct mine, please do so. 🙂

[One link corrected in edit by Robert]

LikeLike

Sorry, Amstel = Smaragd in my second remark.

LikeLike

Hey hanneke28 I have another question you may be able to answer.

Clearly I’ve told a simplified story in this article about parking – as part of highlighting a set of overarching principles and designs which define the Dutch way of doing things.

I’ve suggested that the places you can park are marked (and you can’t park elsewhere) – contrasting this with the UK approach, where yellow lines are painted on so many of our streets – and where (generally) the absence of a yellow line means parking is allowed.

The system is fairly clear on the Dutch ‘old town’ type streets (as you label them). However when you travel further from the city centres – or to less dense cities/streets – the system seems less clear. Here for example: https://goo.gl/maps/kQ2zyDVoQir (Rotterdam) it can be seen that parking takes place along the edges of the road. Some of the parking spaces are not marked.

How is it that people understand that they can park a car here? What are the rules – presumably there is one about not parking on the junction itself? There is a ‘no parking’ sign which seems to suggest that it is not allowed to park on the one side of the road. Would people clearly understand that this sign only applies to that side?

Or is the system as confusing to Dutch people as ours is sometimes to us? Do you need to be a local person to understand the rules?

Your comments on this would be welcome.

LikeLike

If I recall correctly (I have a Dutch drivers license, but rarely drive), it’s a combination of two things, on top of the fact that you can park ‘anywhere’ sensible. The first is that you can’t park near intersections (5 meters away I think) or pedestrian crossings etc, the second is that when there are explicit parking spots like in your designs, you must use those and cannot park outside of them.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Cycle Bath and commented:

This is simply brilliant

LikeLike

Excellent work as always.

I feel like you’ve underemphasised the importance of truly blocking off through-routes to cars, aka filtered permeability. Without that you may copy the Dutch look and feel but you’ve still got rat-running. Whereas Cambridge has made a lot of progress with filters and without changing the tarmac-dominated British street environment. It’s not as nice as the Dutch examples but it functions, and could be easily deployed within current practice.

I also note that many recent developments based on Manual for Streets seem to pull out the ‘shared space’ fancy-surfacing card when they can and still end up being car-dominated. They don’t compare to the play-street my friends live on in Utrecht, which has a shared surface of bricks: with trees, plantings, benches, playground toys, cats, children playing, bikes leaning against houses and a surprising number of parked cars in staggered arrangements. One thing I was reflecting on recently there was the way everyone’s house had enormous front windows right on the street and very few people drew their curtains closed. I think that is an indication of how people feel more connected to the street in front of their house.

Although to bring up another Cambridge example, some streets in Arbury were done with some carriageway narrowing like I note in your examples. https://goo.gl/maps/jYcrBZGVPmx

However you can also see some important differences, such as still overly-wide roads away from the junction, too much tarmac, and too many road lines that are ignored anyway. The build quality is horrid as well. Then looking at the buildings: they are behind fences and car parks or some with bushes, the houses having small windows in the usual style.

Speaking of street build quality – something that always astonishes me after hundreds (maybe thousands?) of miles of riding in the Netherlands is the amazing quality of the workmanship. All the concrete tiles line up and are flush, with no distortion. Mostly the brick roads are too. Riding across changes in surfacing is smooth, no tricky upstand to navigate. There are very few potholes, even on countryside roads in out-of-the-way. I really cannot imagine that being achieved here. I would love to know why.

Another thing I need to learn more about is the way that works are done by utility companies. Here, a statutory undertaker can come along and dig up your road in whatever slipshod manner they please (regulations, what are those?), then dump some tarmac and be-on-their-way. There’s some ‘lovely’ trench-shaped potholes in my street as of recent work. I can’t imagine that same funny business takes place over there, there’s no evidence of it.

I have seen utility companies at work in the NL and being inconsiderate too – parking on the cycleway or blocking the footway – so it’s not necessarily an excess of politeness.

LikeLike

Matthew – thanks.

I’ve intentionally not bothered mentioning that the Dutch system does make some use of the kind of ‘filtered permeability’ that we have. I think that’s fairly well understood. But what I observe is that the Dutch system makes relatively sparse use of the kind of filtering that the UK uses. There are places where bikes can get through, but not vehicles, but often these are because of features being added for bikes, rather than odd bollards being added to block cars (etc). That’s not a rule of course – I have some excellent photos of places where chunks of street are taken out of the system for larger vehicles, while remaining passable by bike. Again though, the Dutch system is to make something of these spaces, not just to add a bollard or two. Perhaps there’s another blog post in that…

What’s hardly understood at all in the UK (as far as I can tell) – which is why the emphasis here (I hope) – is that the one-way systems achieve the same ends – ‘filtered permeability’ if you like, but not really with any kind of ‘filter’ as such.

I agree with much of the rest of what you’ve said. Yes, I also see people managing to create entirely car-centric streets while trying to create something more people friendly. I never know if it’s incompetence, willful ignorance, the seeking of a simpler road layout, or what… but people do seem to think that simply laying a different surface and removing footways will naturally make for a people-friendly space. Often it just creates something that feels like a car park. What tips things one way or the other is subtle.

Mark Wagenbuur writes about the quality of Dutch roads and paths here: https://bicycledutch.wordpress.com/2014/05/15/denbosch-before-and-after/

My Dutch colleague (now in New Zealand) spoke a lot about how much effort was put into building roads properly in the first place, and repairing them properly when that was necessary – the philosophy being that this is cheaper in the long run.

I also have questions about these things. One main question is whether the street bricks work well when lifted up – and then replaced. Reason says that this is a good system, but I’d like confirmation before I proclaim it too loudly. I also wonder about the presence of such large quantities of sand in the Dutch system – is this helpful, or unhelpful, essential, or irrelevant. I’d like a suitably qualified engineer to bring my knowledge on this up to speed.

LikeLike

Caveat: I’m not an engineer, even though I took one short civil engineering course in street design decades ago. This is my layman’s understanding, and I hope a real Dutch civil engineer will chime in and correct me. Still, until you get a better answer, I’d like to try and answer a few of these questions.

Taking up, cleaning (often by noisy shaking in some kind of hopper, I think) and then re-using the street bricks upside down (the less-worn surface up, unless there’s one side with a special gritty anti-wear & better grip top layer) with a few new bricks here and there to replace the broken ones usually works very well.

Laying the new street is happening more and more with mechanical assistance. First it was lifters that set a prelaid square meter or so in place, now you start to see these machines more and more often. They are very much better ergonomically for the bricklayers, and they get the job done quite fast. Several firms produce these around the world, and the bricklayers can lay any pattern they want (including the parking bays) before it slides down the ramp to rest on the packed sand.

Streets are generally on a refurbishment plan – the town council plans which streets need replacing in which year, and budgets money for that, as well as the general small repairs budget. In my town, each neighborhood gets refurbished after about 30 years, which means taking up the old streets completely (and the sidewalks separately), one or two at a time so people can still get around but have to park around the corner for a few days, or walk their bike for half a street to reach their door. Street plans and parking get adjusted where necessary; the council generally hold public meetings about those changes long before the work starts, so people’s wishes can be taken into account – that includes working with the neighborhood school to get their and the kids’ views.

The council also coordinates this a few years in advance with all the utilities so they can plan to renew their pipes and cables while the street is dug up – if they don’t do it now, they’ll have to wait 30 years for the next refurbishment. Nowadays some extra empty pipes are put down as well, so cable and fiber-optic firms can shoot new lines through those when they need to, in less than 30 years, without digging up the road. Public greenery gets renewed at the same time, (where necessary, of course not all the trees but if some are too old and getting likely to drop branches they can be renewed now) and playgrounds changed with attention to the changing demographics of the neighborhood.

This is also the chance to change the sewer system, for instance putting in separate stormwater drainage that doesn’t connect to the main sewer but gets its own pipes leading to overflow or absorption basins.

The thick layer of compacted sand stabilises the road, but also helps a bit with absorption of rainwater through the cracks between the bricks, I’d guess. Most of the Netherlands is either clay, peat or sandy soil, with groundwater at 60 cms to 2 meters in the low-lying areas, so a road/street that needs to bear weight needs the stabilising sandpack as a base. For highways flyovers and such, on softer ground, you’ll see these huge mounds and ridges of sand put down years in advance, to slowly compress and drain the soil, long before works can start – that slow weight-loading in advance minimizes sinking and damage to the completed viaducts and flyovers later, and probably (my guess) allows the groundwater to find a new balance.

When small between-times repairs are necessary, the council checks they are delivered to a high standard. If one notices a gap or dip in a sidewalk or bicycle lane that is more than an inch deep/high (like a canted, raised or sunken brick because of treeroots or undermining ants) or wide (if it’s a crack), one can phone the council and it generally gets repaired within two days. Repairs will have to be better than that standard to be acceptable!

Many towns use their own version of acceptable standards reference reports for maintenance of public greenery and sometimes of roads and sidewalks, with rules like there must be 10 weeding passes of the public flowerbeds between April first and October 10th, and acceptable and not-permitted methods of weedkilling, but also photographic examples e.g. of how many & how high weeds are allowed to be on which road type and characterization, i.e. more and higher in residential access streets, less and lower in shopping streets etc.. These are used by any greenery maintenance firms who want to bid for these maintenance contracts; and then used by council personnel to check that the firms are performing as promised, if the council doesn’t have the full maintenance staff on payroll.

LikeLike

That’s hardly “just a layman’s understanding” – thank you. Some amazing information in all of that. I keep referring readers to the comments on these blog posts because there’s often as much to be learned here as in the original article.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for all the details hanneke. It is hard to imagine any UK council maintaining such strong standards. Alas.

LikeLike

That Dutch civil engineer mr.Weetman spoke to once was quite right, immediately dealing with small defects saves such a lot of money later.

One maintenance guy with half a bucket of sand and a small spade can re-lay a sagging brick in 5 minutes so the surface is closed and level again, no puddles can form to leach away more sand from the foundation, so the surface can last another 20-40 years without needing major maintenance; and it eliminates a tripping hazard for which the council could get insurance claims if someone falls.

Or for a small crack in asphalt, a ladle of that liquid asphalt repair stuff (instead of a bucket of sand) can stop further deterioration, while if you don’t repair it water gets into the crack and freezes in winter and it’ll be a lot larger next year. It won’t be enough to last for 40 years, but if you repair the first cracks quickly the surface will remain smooth enough for several (5-10?) years so you can plan ahead and budget for larger maintenance dealing with the cause of the cracks (treeroots or sagging foundations) – if it’s caused by heavy vehicles going where they shouldn’t that should be dealt with much sooner; blocking them with a bollard or sending the police or BOAs to regularly inspect and ticket there can be done quickly.

I know our council has a small maintenance team (2-3 people in a town of 60.000 inhabitants, out of about 300 people working for the council in total) that does these little repairs, and changes defect streetlights and traffic lights, and clears fallen branches and trees from paths and roads, etcetera, and that saves enough on hiring contractors for larger repairs that it’s worth it, while it greatly improves the livability of the town.

Not all towns handle these things the same way though, so elsewhere people might have different experiences. I don’t know if the VNG (Vereniging van Nederlandse Gemeenten, club of Dutch municipalities) provides any guidance on this, like “model-beeldkwaliteitsplannen” (standardised models of quality plans with pictures), or if each town invents their own or copies and adapts someone else’s, or does without.

If you want, I can ask at my town hall if they’ve got some examples in PDF that I could send you, but they would of course be in Dutch.

LikeLike

Really like this and would love to apply it. I feel the transition and the level of traffic on the more Urban through roads (at least in London) is a challenge.

I don’t know if you know much about the proposed cycle superhighway in west London but the main road carries a lot of traffic and just the proposal of making a couple of the streets entry or exit only has caused uproar.

I understand if you are at a crawl on the main drag and you are frustrated as you have very little choice but to sit in the traffic to access your local access road but then more people would have bikes if this was in place. It is a little chicken and egg!

What is your take on it if that urban road is carrying lots of buses, taxis, and general traffic. How do we sell that transition phase? Over time it is easy as people adjust the way they move around but getting there is a battle.

LikeLike

What you’re talking about is a whole subject in itself.

If you haven’t yet, take a look at my articles on ‘change’: https://robertweetman.wordpress.com/tag/change/

Don’t be put off by the theoretical sounding nature of this – what I’m writing about in those articles is intensely practical (but it’s hard to photograph ‘change’ or to provide inspiring animations, like with the infrastructure blogs). The point is that what you’re asking about is intensely difficult – the mistake is to think that this problem is one that can be tackled through logic, consultation, or a specific set of tools, and that a clever enough person/process will guarantee success. When I present about this I often use ‘sexism’ as an analogy. How should we go about getting rid of sexism? What process should we use? How do we convince people? Etc. Of course the reason this analogy works is because it makes everyone think more imaginatively. We’d laugh at anyone who told us that given a particular sum of money they could guarantee the end of sexism – it doesn’t work that way. Well neither does the problem we’re talking about here…

So how easy? Not easy. Extremely hard. Key tools? Imagination, vision, persuasion, examples, honesty, openness, trust, belief, speaking carefully, respect, etc etc etc.

LikeLike

Brilliqnt analysis and diagnostic, than you.

A few points, though not to take away from what you say: Dutch water tables are very high and many buildings are piled due to wet ground conditions with reault it is easier to plant large growing street trees in narrow streets. Not so easy on heavier UK soils.

Dutch vehicle users also seem to yield to all cycle and peds crossing urban streets, especially at junctions but also elesewhere in my experience. Not sure if that is their highway code? UK highway code has yield to peds when turning into side roads, but no one does on the whol and even on zebras you have tonstep out to make vehicles stop.

Finally -we have more hills!

Totally agree the traffic cell idea the Dutch use does work well. The same amount of people seem.to move through them, just more walking and cycling.

Re. segregated cycleways, my suggestion is that we design these on a transect basis rpughly based on vehicle speed and urban context i.e. centre of town shared cycle-vehicle slow streets, on street cycle lanes in suburbs and segregated lanes out of town on faster roads.

Suggeat you write Manual for Streets 3..!

LikeLike

(Sorry David – this was stuck in the spam filter for a day. Now published.)

LikeLike

Answer for David re giving way in Dutch highway code.

There are three main rules (and a few minor ones) about giving way, that operate in all situations which aren’t signed differently.

1) Give way to traffic from the right.

Traffic includes bicycles (and horses, and pedestrians, or whatever)!

This even works when two cars are turning into the same road from opposite sides: the car on the right mid-junction goes ahead first.

Fifty years ago we still had another rule which complicated this somewhat, namely that slow traffic (pedestrians, cycles, horses, carts, scooters and mopeds) had to give way to fast traffic (cars, buses, motorcycles, trucks and pedestrians, vans, trams and trolleys). That rule has been nullified several decades ago, simplifying the right = priority rule; the only one who still always gets priority over all crossing traffic is the tram.

2) Traffic turning off a road gives way to traffic going straight ahead – this includes cyclists even on separated parallel cycle paths and pedestrians on sidewalks.

3) Traffic entering a road from an ‘exit construction’, which generally has a level difference (or sometimes the painted row of ‘sharks teeth’ yield signs), like a 30km/h side road where traffic has to bump up over the continuous footway and cycleway and then bump down to reach the main road, gives way to any traffic on the main road (even if it’s coming from the left). This too includes cyclists and pedestrians on parallel cycle paths and pavements alongside the main road.

This is the same rule as for any literal exits from driveways and parking lots and industrial lots.

Simply: If you’re coming down from a speed bump to a crossing, or exiting a parking lot or driveway to a road, you give way.

4) If a road obstruction means taking turns with oncoming traffic to pass the obstruction, the car on the side of the obstruction should wait until the oncoming side is clear. This is one rule I’ve lately noticed a few younger drivers ignoring, instead speeding to see if they can pass the obstruction first…

5) Zebras: if a pedestrian on the sidewalk looks as if they might want to cross on the zebra, the car driver has to stop, i.e. even before the pedestrian steps out. The same rule applies to pedestrians on zebras and cyclists, but those generally mutually negotiate their way with a slight decrease or increase in speed and a slight swerve, without needing to come to a full stop.

Any pedestrian can cross anywhere, as far as I know (there’s no jaywalking law, but I’m not sure if there might be rules about not randomly crossing within 20m of a signalised pedestrian crossing or something like that), and the heavier/faster vehicle always has a duty of care towards the more vulnerable road user. For cars that just means stop, don’t run over crossing pedestrians. Bikes have more flexibility to swerve and change their speeds to avoid those crossing.

LikeLike

Excellent analysis of both you Robert and Hanneke about the basics in The Netherlands street scaping tradition, since the invention of the so-called woonerf (traffic calming) in 1970 in the city of Delft. The battle of fighting car dominance in Dutch cities & towns is a long one…

LikeLike

Thanks 🙂

LikeLike

Answers about parking rules in the Netherlands (to the best of my abilities; I’m no policeman).

Unless there is a no parking sign, one is allowed to park alongside the pavement.

If there are parking bays, one is expected to use those first, and generally not to park along the pavement outside of those unless all the parking spots are full (on pain of getting into arguments with the neighbors, not in legal trouble).

In the residential areas with narrower streets people quickly come to a concensus on which side of the street they’ll park, and on which they’ll drive, as the street is only two cars wide; so unless everyone parks on the same side it becomes an impossible slalom and nobody drives – sometimes these sides switch, if it’s bin day or somebody gets stubborn, but that doesn’t need a no-parking sign on one side of the street. Nor marked parking spots really, if it’s only used by the people living there, except those add the option of reserving some space in between the parked cars for other things like trees or bike parking (or unless the street is within a parking restricted zone of type 2 mentioned below). Which is why a street like Woestijnvaraan, despite the narrow carriageway, has no parking bays or restrictions – there’s plenty of greenery beside the carriageway, and the houses all have bikesheds in their gardens (the narrow paved strip opposite is for the bins on bin day 🙂).

No parking signs are only applicable to the side of the street on which the sign is placed (unless they’re zone signs, as I mention later on): if you want to forbid parking on both sides you put up signs on both sides, in both directions = four signs, two at the entry (on both left and right pavement) in one direction and two at the opposite entry. Sometimes they have little arrow signs indicating they’re only applicable for the part of the street indicated by the arrow, e.g. from this pole to the right-hand end of the street is no parking.

Like this repeater sign halfway along a street, for anyone coming out of the sidestreet. In this case, no parking on the tree side might be meant to protect the tree roots, or done because otherwise cars parked far enough apart ordinary cars could slalom slowly through, but the fire truck or bin truck couldn’t.

In your example, with the apartment building along that street, there probably aren’t enough parking bays for everyone.

There was a time (in the nineties IIRC) when national policy tried to discourage car ownership and use by mandating building inadequate numbers of parking spots for new dwellings – a maximum of 1.5 per house is the stat I recall, but what the number was for apartment buildings I don’t know. They stopped mandating those maximums after a 4-8 years, but whatever got built in that period got stuck with too few spots for a long time. There’s one garage per 4 apartments in your example, and cars parked lengthwise mean you won’t fit three more per appartment length on one side of the street. No-one has their front garden on that street as no-one lives on the ground floor, so you won’t get into arguments with the groundfloor inhabitants over blocking their view. Some will park around the corner, but a lot won’t.

In a 20-40 year old neighborhood, when all the young kids born after their parents bought their house have grown into students with driving licenses, but haven’t completely moved out, there will generally be a period when a lot of families own more than 1.5 car, and the number of marked parking spots provided won’t be enough. During that time, you’ll see a lot of cars parked along the pavement opposite, but after that the kids move out, then people get their pension and stop “needing two cars for separate commutes” and car ownership declines, and then the neighborhood diversifies when some empty-nesters move out and new young families move in, and generally the marked parking bays will be enough again, unless someone is having a party.

One is not allowed to park within 5 meters of a corner: this is not marked with your double yellow lines, it’s in the Highway Code that this is never allowed, one of the things one learns during driving lessons.

One is also not allowed to park on any part of the right-of-way that is meant for other categories of road users: not on pedestrian pavements, cycle paths or lanes (or even beside them, unless in marked parking spots), bridle paths, bus lanes, or anywhere it might cause a dangerous situation, like in a junction.

Here’s a link to a page in Dutch with the rules regarding where one is not allowed to park, or to stop and park: http://www.gratisrijbewijsonline.nl/parkerenwet3.htm

The most common parking restriction zones in the Netherlands are:

1) Blue zones, marked with a sign giving the maximum allowed time and with a blue line along the edge of the pavement (where you can park for a limited time by putting a blue time-clock thingy in the car window).

2) No parking anywhere except in marked parking spots. This is often used in city and town centers, to stop people parking alongside the pavements in narrow or crowded streets. It’s seldom used in residential areas, except maybe around schools if there are starting to be too many drop-offs and pick-ups by car; in that case there’s often a time period marked during which the restriction is in place. This is marked by a no parking zone sign with the sub-sign “alleen in de vakken” (only in marked spots), or by the parking-sign with a similar subtext, in this case accompanied by a warning your car will get towed if you disregard the rules.

3) No parking except for license holders (“vergunninghouders”, in Dutch), which is mostly used around shopping centers or train stations to make shoppers use the (paid) car parking at the shopping center/station instead of parking for free or causing trouble in the surrounding streets.

4) No parking for heavy goods vehicles within the built-up area signs, on the entry roads into town, so truckers have to leave their trucks on an industrial estate instead of taking them home for the weekend.

I think that’s it; sorry for going on and on again. I may be belaboring the obvious here and there, but as I don’t know what is obvious to you I’ve tried to put it all in.

And please remove the first of these double posts awaiting moderation, as I made a mistake in a link.

LikeLike

I found a better link to a Dutch page with all the rules about parking and stopping, with less pictures but clearly enumerating not just the rules for stopping (as I linked above) but also for when parking is forbidden but stopping is allowed (within 5 meters of a junction corner, at an entry/exit, on a yellow line, in a loading zone or double-parked, or on the carriageway of a rural 80 km/h priority road): https://auto-en-vervoer.infonu.nl/verkeer/9873-regels-stilstaan-of-parkeren-met-de-auto-op-de-openbare-weg.html

One other thing that might be different in the UK, regarding parking restriction zones: once the zone is marked by signs at all the entry and exit points, the no parking signs do not need to be repeated within the zone itself, and certainly not on every street.

Sometimes an occasional reminder is placed, but to eliminate unnecessary street clutter these repeater signs are kept to a minimum.

The one repeater I linked above is not part of a restricted zone (as far as I know), it’s just the one street, which is why people entering from the side need a reminder.

So all those streets in the town center where everybody only parks in marked parking-spots are quite likely to fall within a town center zone where parking is only allowed in designated parkingspots (zone type 2 or sometimes 3 in my response above). You wouldn’t find a no-parking sign at the start of the street, in that case, you’d only find it if you retreat to the edge of the center zone. Everybody who enters that zone by car should see the parking restriction zone sign, and should be aware that they haven’t yet passed a sign denoting the end of the restriction zone, so constant reminders are considered unnecessary. No specific local knowledge is necessary, but paying attention and remembering is.

LikeLike

Thank you again. I really appreciate this (and I hope other readers do too). Here’s a Google Translate version of the link above: [ https://translate.google.com/translate?sl=nl&tl=en&u=https%3A%2F%2Fauto-en-vervoer.infonu.nl%2Fverkeer%2F9873-regels-stilstaan-of-parkeren-met-de-auto-op-de-openbare-weg.html ]

LikeLike

hanneke28 – that’s a wealth of information on parking – just what I was asking for. Thank you so much.

It’s interesting that this set of rules would appear fairly similar to ours – but that the result is so different. As I said above, I’ve told the story in simple terms in the blog post – but the result of your rules is so different to ours. We have a situation where yellow lines are painted everwhere – where local authority officers responsible for the design of the streets decide that these are needed even where it makes the infrastructure difficult to understand. Here, for example [ https://goo.gl/maps/fUs3Ket83n32 ] it should be clear that the people cycling can continue ahead onto the path – but we paint the yellow lines across the path to stop people parking here. The argument is that even if we left 2 metres without lines, people would park here – which means that people cycling feel as if they are always going on and off the road – on and off ‘pavement’ (i.e. footway) – for one moment being asked to pedal furiously to be like a car, and then the next moment being asked to pedal gently, so as to be like someone walking. It’s such a simple thing, but the effects are profound I think.