Amsterdam vs Copenhagen…

…Netherlands vs Denmark

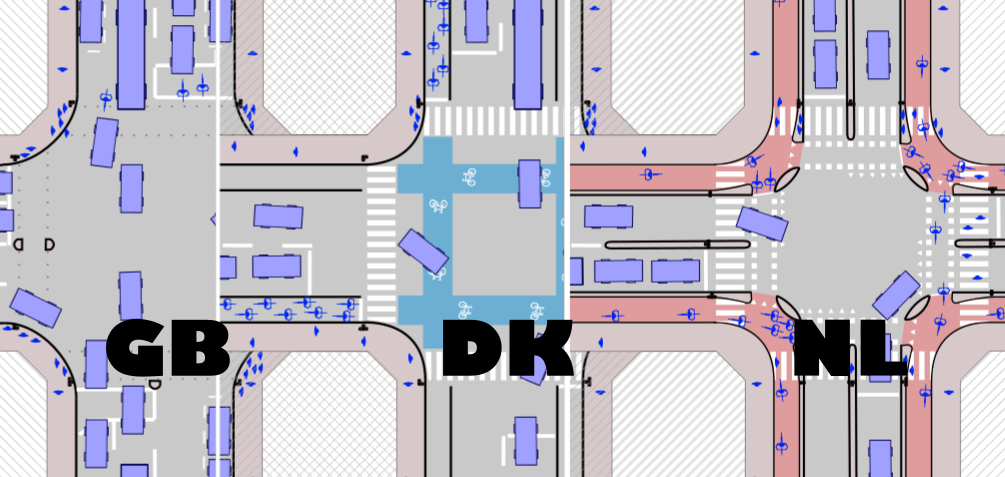

Part 2 – Basic junction anatomy

Here I’m going to provide some sketches of junctions which are designed to make it safe and easy to cycle (they support those on foot too). The first part of the series looked at differences in the design of basic cycle tracks – and here I want to discuss what happens when roads with cycle tracks meet.

This 3 part series is spread over three separate blog articles.

Link to part 1 (basic cycle track anatomy)

This is part 2 (basic junction anatomy)

Link to part 3 (Who wins? Which approach is better?)

Individual junction designs are often very different from one another. If you follow the Google Streetview links in this article you’ll see that few of the real situations show something exactly like the drawing I’ve provided. What I hope to explain here are some features that make a Dutch junction feel like a Dutch junction – and a Danish one feel like a Danish one.

Take note that the previous warnings still apply (as in part 1).

What I’m aiming for is to convey my overall impression of the differences in infrastructure design. The images in this post are simple sketches, illustrating my overall impression of the differences in relatively standard infrastructure in each place. These images are not to scale, and almost certainly contain errors when compared to real infrastructure. What I’m drawing here is simply a set of idealised images, intended to convey the differences in general approach which I’ve observed during my visits.

You’ll detect that I tend to talk about Copenhagen rather than the whole of Denmark. My knowledge of Danish infrastructure is more limited than my knowledge of the Netherlands so I can’t easily speak of other main cities.

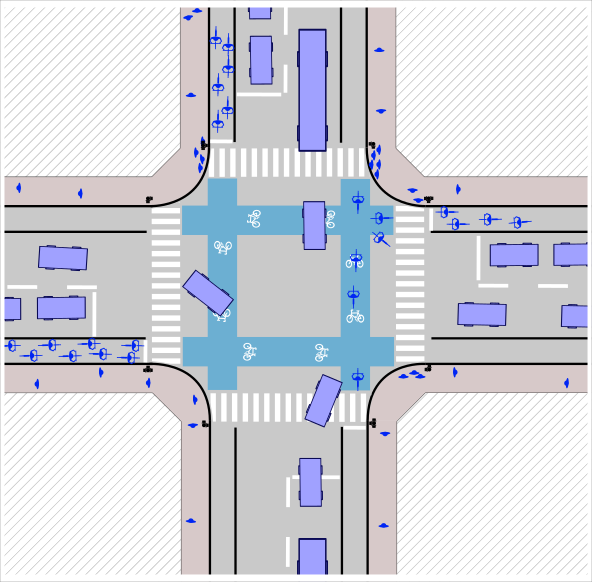

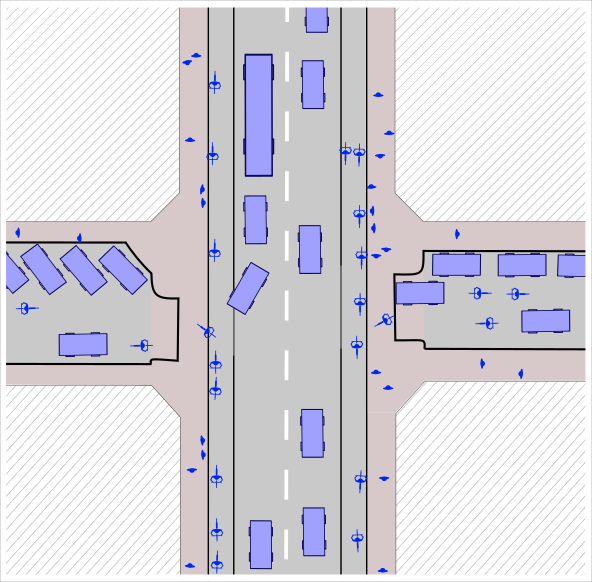

1. Copenhagen: major junction

Here is a junction where there is provision for cycling on all the branches of the road. This occurs typically where two important roads meet. In both the Netherlands and Denmark (certainly in Copenhagen) we’ll expect to see that cycling is accommodated through the junction in one way or another.

(Open a full screen larger image using this link.)

The principles I’m illustrating here tend to apply across various different sizes of junction – the design principles apply even when more lanes of traffic are present than I show.

We can see the following in the design – note that these points are picked up in the next section to provide a comparison to the Netherlands:

(NB: If you are viewing this on a small screen try with your device in both landscape and portrait orientation to check which makes it simplest to see/read the images/text)

The segregated provision for cycling – the cycle track – stops before the space where pedestrians cross and re-starts after passing the space where pedestrians cross (as you leave the junction).

The stop line for those cycling is close to (but often ahead of) the stop line for those in motor vehicles.

If you want to turn right here you have to wait with all of the other traffic/bicycles.

There is wide painted blue stripe across the junction signifying the route taken by those cycling.

Those wishing to turn left at the junction do so in two stages (explanation on cycleguide.dk). I’ve read that this is required by the rules, but I’ve also read that it isn’t.

People cycle across the first arm of the junction and then show an ‘I’m stopping’ hand signal (explanation on cycleguide.dk) – moving slightly to the right, then turning to point across the second arm of the junction. There are two people in this drawing who have done this.

I’m assuming (but didn’t check) that the branches of the junction are released in a sensible order, minimising the wait.

The rules, conventions, and habitual practice, mean that those turning right in motor vehicles wait for those travelling ahead on a bicycle.

People really do this – it’s not just the rules.

People waiting to walk across the road do so on the footway, and have to cross all of the road (including across the cycling part) to the opposite section of footway.

Here are some Google Streetview locations showing junctions which are roughly of this nature. The details are not all the same on all of these – look carefully for where the real junctions are different to what I’ve drawn.

Streetview: example A1 / example A2 / example A3 / example A4 / example A5 / example A6

Use Streetview to have a wider wander around Copenhagen to look for these features yourself.

While using Streetview you’ll also notice that there are still many junctions between major roads there where no provision has been made for cycling at all, or where it only exists on one or two branches of the junction.

Streetview: example B1 / example B2 / example B3 / example B4

On Streetview you’ll also encounter a relatively common feature where there is a merging of right turning vehicles with bicycle traffic (where the bicycles are going straight ahead or also turning right). Those cycling join the motor traffic temporarily. This is a way to manage issues with right turning vehicles.

Streetview: example C1 / example C2 / example C3 / example C4

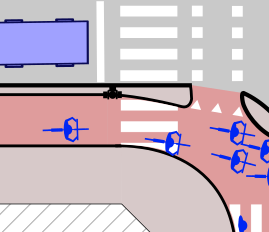

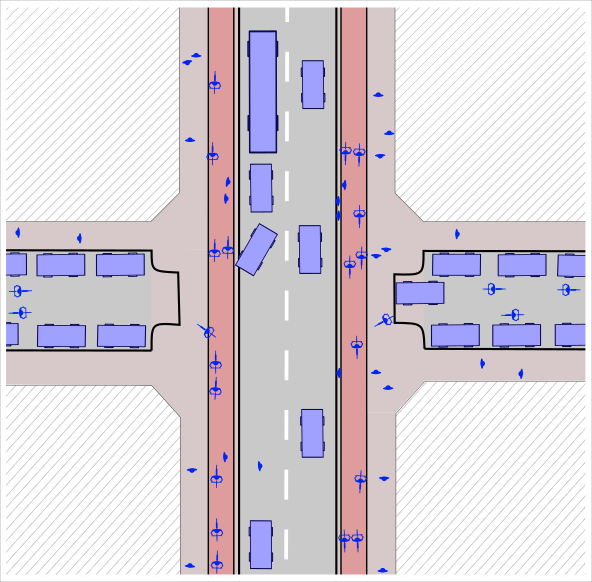

2. Netherlands: major junction

This is a typical/stereotypical main junction in the Netherlands. This drawing has the same dimensions as both the Copenhagen example above and the UK junction at the end of the article.

(Open a full screen larger image using this link.)

We can see the following in this design – compare each point with the Copenhagen design above:

The segregated provision for cycling – the cycle track – continues through the place where pedestrians cross. There is a zebra crossing (often with no signals) across the cycle track. In theory pedestrians have priority here, but in practice there’s some give and take and (rightly or wrongly) there is a relatively relaxed attitude to this from all involved (people on bikes also don’t get upset if you cross in other places so long as you don’t stand in the way on the cycle track).

The stop line for those cycling is on the edge of the road to be crossed (those waiting to cross from left to right in this image). This makes for a much narrower stretch of unprotected cycling – the actual distance that people travel on the roadway is minimised.

If you want to turn right here you don’t have to wait with all of the other traffic/bicycles – this only involves crossing zebra markings (with no signals).

The path for bicycles crossing is marked with painted white ‘elephant’s footprints’.

The rules, conventions, and actual habitual practice, mean that those turning right in motor vehicles wait for those travelling ahead on a bicycle, or crossing on foot (unless the junction is intentionally designed differently).

There is also the use of triangular ‘sharks teeth’ markings in white paint. These are used in any places where it is necessary to explicitly indicate who has priority.

The sharks teeth markings are used in multiple situations. Here in the drawing those travelling (from right to left) on the cycle track have priority over those joining the track from the road. Sharks teeth markings work very well to show fine details about priority.

Sharks teeth markings also help to make it very clear which direction bicycles should travel on more complex junctions – so helping to make clear what is and is not for one-way use. In this drawing the sharks teeth make it obvious to those on the cycle track that they should not turn left here.

People waiting for signals to walk across the road do so on the outside of the cycle track, having already crossed the cycle track, with a much shorter section of road ahead of them. Take note that I didn’t draw this very well – I’d expect a larger area to stand on.

At the point where people are crossing the road they are well away from the swept corner (so they step onto the road and are walking at 90 degrees to the kerb – compare this with UK design where people often cross at the curve of the road).

I also added a central refuge/island to this drawing. I’m not sure that this is so accurate for a road with only two lanes, but it seems to me that Netherlands designers are generally more willing to narrow traffic lanes like this – perhaps not least because the cycle tracks are protected at this point. Often there are several such refuges/islands where a junction involves multiple lanes of traffic and provision for trams too.

Here are some Google Streetview locations showing junctions which are like my drawing – or mostly like the drawing. The details are not all the same on all of these – look carefully for where the real-life designs are different from those I’ve drawn.

Streetview: example D1 / example D2 / example D3 / example D4 / example D5 / example D6 / example D7 / example D8 / example D9

(Alexanderplein: I’m aware that the infrastructure shown in example D1 has been re-designed since the Streetview photographs were taken but it illustrates this design nicely.)

Use Streetview to wander around a town or city in the Netherlands to reach an understanding of how common these designs are (or aren’t) in comparison to the alternatives.

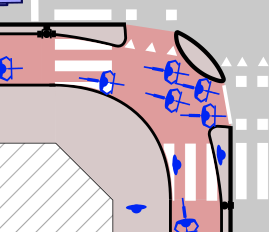

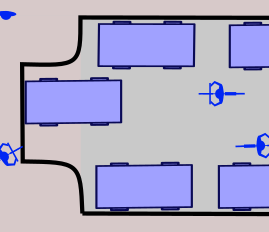

3. Netherlands: side road junction

Clearly there are situations where a road with a cycle track crosses or passes the end of a smaller road which does not have a cycle track.

This time I’ll start with the Netherlands image.

(Open a full screen larger image using this link.)

In the Netherlands there is a standard and very common treatment for such a junction which involves the cycle track and the footway carrying on across the end of the smaller road.

You can see the following:

The border between the cycle track and the road remains – and this usually involves a distinct sharp short ramp. The cycle track is flat but raised above the road level.

The kerbs on the side road narrow the side road before it meets the footway – creating a helpful visual effect, slowing turning/exiting traffic, and reducing the space in which those on foot and cycling are more vulnerable.

The side road is specifically designed so as to be narrow, actively slowing vehicles. It carries two-way cycling, but one-way motor vehicles.

Those driving (who almost certainly also cycle sometimes) reliably wait for people on the cycle track or walking on the footway. Visually it is completely clear that this is footway/cycle track space and that the person driving is not on a piece of roadway. There are no painted lines, no changes in paving, nothing to suggest that they can drive here (other than the fact that they can see a roadway on the other side of the footway).

I’ve heard various names in the UK for this design – I prefer ‘continuous footway’. I don’t call it ‘continuous cycleway’ because the design is also used regularly when there is no cycle track. This isn’t just a way to prioritise cycling, but also to make the city MUCH more friendly for those on foot.

In the Netherlands this ‘continuous footway’ has a secondary purpose – not so obvious to observers from outside the country. It indicates to those driving into the quiet side road that it is a quiet side road. It’s a ‘gateway’ feature. People driving know that once they pass into a side road over the continuous footway that they should expect a radically different design of road. This signals that on the side road they may have to drive very slowly, and where priorities are shifted so that those on foot and on bikes are quite likely to be in the roadway.

The one-way roads are also likely to be arranged so as to prevent through traffic – meaning that the only people driving into these roads are doing so to reach/leave a property on these roads – radically reducing traffic levels.

Below are some Streetview images of this kind of junction.

Streetview: example E1 / example E2 / example E3 / example E4 / example E5 / example E6 / example E7 / example E8

For lots more detail on continuous footway see Design Details (1)

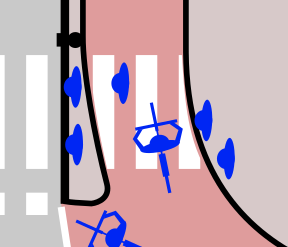

4. Copenhagen: side road junction

In Copenhagen the same continuous footway feature can be seen. It’s less common, and really good examples are rarer, but it is still used extensively and is very effective.

(Open a full screen larger version using this link.)

We can see the following – which are worth comparing to the Netherlands design:

As in the Netherlands the cycleway and footway both cross the end of the side road. And as in the Netherlands the width of the side road often decreases – for visual effect, making turning speeds slower, and making the area where people (on bikes or walking) are vulnerable much smaller.

Because the cycle track is only separated from the roadway by a small kerb (and a slight height increase) there is no ramp – however the kerb continues. It may be reduced slightly in height. There are also occasions where the kerb may be removed and a blue stripe may be added to highlight the cycleway instead – or where the kerb is higher a tarmac ramp may be added.

It’s much more likely in Copenhagen than in the Netherlands that the side-streets will carry two-way traffic. They may well be designed so that even at the entrance to the side roads there is space for two lanes of traffic.

Here are some Streetview images of continous footway (and similar) in Copenhagen. Not all of these are good examples. Look back to the Netherlands for the better designs.

Streetview: example F1 / example F2 / example F3 / example F4 / example F5 / example F7 / example F8 / example F9

Have a wander around Copenhagen using Streetview. Take note that in comparison to the Netherlands there are many more busy/fast two way ordinary streets where there is no provision for cycling at all.

5. But now the important bit

So you thought that this post was all going to be about fancy junction designs like those above? Actually these fancy designs could distract you from what I think is really important.

This is specific to the Netherlands.

Go looking in Google Streetview – at Amsterdam or Utrecht – for the Dutch junction designs I’ve drawn. You will find junctions that look like what I’ve drawn. They are fairly common. And you’ll see all sorts of other arrangements. And there’s no denying that you’ll also see some sub-standard infrastructure – for example some painted cycle lanes.

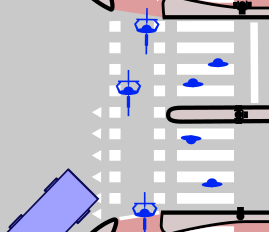

BUT what you’ll see most is junctions which don’t have any obvious provision for cycling at all and which might look something like this:

(Open a full screen larger version using this link.)

Firstly take note that I’ve not drawn any moving motor vehicles. The streets are arranged – in particular with the one-way system – so as to make them useless for through traffic. A network of such streets is often bounded – where it meets main roads with two way traffic – by junctions with continuous footway (with or without a cycle track) as in section 3 above. This means that the roads are quiet (in all senses).

People can walk on these streets with little risk.

The junction design itself includes a ‘raised table’ – where the road level rises to slow traffic. You can see the standard marking for the ramp.

The roadway is narrowed. Those on foot have a much reduced distance to cross.

Because of this the corner is very tight making traffic travel very slowly.

And there’s lots of other stuff going on here. There are signs of life and habitation. There’s greenery – lots of plant life. There might be places to sit. There may be bollards. There are probably parked bicycles. It’s all a bit cluttered – and generally that’s a good thing. Some of these junctions and streets can feel like an extension of the living space for the residents. It’s clear that people live here and that you’re driving/cycling in their space.

To my mind THIS is by far the most important junction design to remember when you think about what makes cities in the Netherlands what they are. It’s not so pretty to draw because there aren’t any cycle tracks and not much white paint – and this design might easily be forgotten – but it is incredibly important.

This doesn’t look like infrastructure designed to support cycling, but what’s going on here IS very important for the support of cycling. AND this kind of urban design is also incredibly important for making the streets nice to walk in (or to sit in, stand chatting in, play beside, wheel through, and so on).

UPDATE: Since writing this I’ve added a much more detailed, dedicated article (I want my street to be like this) discussing these junctions and the wider Dutch treatment of residential areas. It even has pretty animations to explain why this is so important.

Take a wander on Streetview. Remember THIS design may be the important one to remember.

Streetview: example G1 / example G2 / example G3 / example H4 / example H5 / example H6 / example H7 / example H8

6. Oh… and then there’s the UK…

So to finish. Here’s what a standard level of support for cycling looks like in the UK. The same can be seen in many other countries. I’ve fitted four lanes of traffic into this space – it is exactly the same space as shown on the main junction designs for the Netherlands and Copenhagen that I drew above.

So that’s not very exciting… where’s the infrastructure supporting cycling?

Well what I’m presenting on this article are diagrams which show how cycling is typically dealt with at junctions in each country. This, above, is typically how cycling is dealt with at junctions in the UK. The standard infrastructure ignores (or almost ignores) cycling. People on bicycles have to mix with the other vehicles.

Of course there are exceptions. There are a few places in the UK where some (relatively) good designs have been built. But they are very few and there is no typical design. Even where there is some provision for cycling it is different in every city, and on every junction within a city. And often whatever is there is only just worth having at all.

I should say that I’m not trying to put people off cycling in the UK. I should remind everyone that this failure doesn’t make it impossible to cycle safely in the UK. If you’re prepared to take a long route to your destination – to get off and walk sometimes – and generally to behave like a rat running around behind the skirting board (i.e. behind the wall of a room) then you can get to your destination safely, fairly quickly, and maybe even enjoy the trip.

One of the people using bicycles in this drawing is doing this – they are walking. That’s slow, but not as slow as waiting for the signal. It also carries some risk – the pedestrian ‘reservation’ in the middle of the road isn’t quite big enough for the bicycle so the person is needing to be alert and watching for danger.

There’s also someone fighting for space… being squeezed between the back of a bus, parked cars, and a following car.

They will be OK because they are fit and fast. An older person or a child wouldn’t do this. You can tell that the person is probably wearing lycra, and they will need to have a shower when they get to work.

I’ve drawn two branches of the junction with ‘advanced stop lines’ – a space where those on bicycles can officially stop in front of stationary traffic. Arguably this is better than nothing at all to support cycling. Take note that the vehicle has encroached into this space and is close behind one bicycle. Also note that to get to this space those cycling have had to squeeze between this car and legally parked cars. We allow the need for people to park cars to be placed above the need for the safety of those walking and cycling.

And this isn’t much good for those on foot either. There’s a whole lot of waiting around. When you cross you’re doing so at a point where the kerb hugs the building – ensuring that people can drive around the corner with as little inconvenience as possible.

In the UK we tend to strive for every possible road to be allowed to carry as much traffic as possible.

Importantly what this means is not just that ‘main’ junctions are designed in the way above – but that many more junctions are treated as ‘main’ junctions. In the Netherlands and Copenhagen lots of connecting roads are treated as minor side roads (perhaps with the designs above). In the UK these are treated as main roads – dedicated to through traffic.

So we don’t just get this horrible main-junction design in places where in the Netherlands and Copenhagen there would be a good main-junction design – we also get a lot more ‘main’ junctions.

Lastly I’ve drawn that someone chose to cycle on the footway (UK “pavement”).

It may also be that cycling is actually allowed somewhere on one or two of the footways that I’ve drawn. There may (or may not) be some signs to show this. Some of the crossings may also allow cycling. It may even be that a ‘toucan’ crossing – where it is legal to cycle – ends on a footway where it is illegal to cycle.

Or it may be illegal to cycle here. It can be difficult to tell. I have professional expertise on cycle signage and I know the legislation/rules very well. But sometimes even I can’t work out from the signs where it is legal to cycle and where it isn’t.

So that’s the UK. No standard practice. No normal way to support cycling. We haven’t even decided on the colour we’re going to use to indicate cycling infrastructure yet (whereas there are pretty standard colours in Copenhagen and the Netherlands).

Part 3, once I’ve written it, will probably compare the overall effect of the differences I’ve discussed in parts 1 and 2. Watch this space. In the meantime there are lots of other articles on this site.

Lastly – for those people who know one of these countries well I have a request. Please let me know if you think that I’ve got this right (or if I haven’t). If you can provide further information then please do use the comments. People can read these to check what others think, and I may also update the article if I learn of any big mistakes.

See also…

- Amsterdam vs Copenhagen (part 1)

- Amsterdam vs Copenhagen (part 3)

- I want my street to be like this (on residential local access streets/areas)

- Design Details (1) – Continuous footway. Side-road crossings. Simplicity and clarity. Getting it right. Getting it wrong

- What nobody told me (about Netherlands urban design)

- Copenhagen bus stops

- Read everything – New here? This is a suggested reading order.

Comments…

- Scroll below for comments.

If you landed here from a Twitter link on a mobile device you may need to press ‘Leave a comment’ below to see the comments on this article or you can reload the page to see them.

Excellent. Was very much looking forward to this and didn’t disappoint. Think you’ve very clearly demonstrated the principles each country embraces in planning junctions. You’re right that maybe the ones shown are idealised but they show the theory behind the thinking very well. I am from UK and live in Amsterdam now (and have cycled and driven all over both) and have some limited experience of DK, and think you’ve nailed it. I can see your NL major junction from my apartment (with addition of tram line on both roads), and can name half a dozen of both the other NL types within a few blocks. Note the quietway junction often is or is approaching a primary school, showing its effectiveness IMO. My biggest fear in the UK example has always been approaching this all too common junction from the bottom road, I assume the left lane will be left turn only priority at junction yet you’re expected to cycle at the left of traffic then somehow veer to the right across following traffic to go ahead. An important component of the success of NL and DK junctions, and inadequacy of UK ones, is also the signalling sequence (including traffic light sensors and cycle lane buttons), and the way UK does not allow turning into a crossing the way most other countries do. Looking forward to the next one!

LikeLike

A master piece !

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you. It took more effort than I’d anticipated but this one has been itching to be written since we returned from Copenhagen. Glad you liked it.

LikeLike

There’s a very interesting book about what you describe as “Signs of life and habitation” in a lot of Netherlands streets written by a French architect and urbanist named Nicolas Soulier : “Reconquérir les rues” (2015).

LikeLike

Unfortunately, having had a British education, my foreign language ability isn’t up to a French book. You don’t know if there’s a translation do you? Has anyone summarised the content or written something you’d compare to this in English?

LikeLike

Great series of articles.

The lack of cycle infrastructure in UK cities and inconsistency even when it does is maddening. Here in Newcastle where they’ve introduced dockless bikes too, it’s very inconsistent.

Why such bad new design when there good examples to be copied. ?!

LikeLike

Thank you. I have in mind that part 3 may include some discussion over how we might work toward some consistency – how we might decide what would work best on UK streets. But we’ll see…

LikeLike

I’m from Germany living close to the NL border. In Germany it’s very common that people turning right don’t look over their shoulder to check if it’s okay to turn. You always have to pay attention and sadly almost every day people get killed by cars, lorries or busses. In the NL however, people drive very carefully always checking ahead. You also mentioned one of my most loved elements: the shark tooth. In the border region they can sometimes also be found on the german side which very nice, because it is more easy and intuitively to understand and also faster to recognize and process by the brain than the variations of priority signs. Cycling in NL you can let your thoughts drive away without getting injured or killed, whereas in Germany it is very likely that you will have a bad day when not paying crazy attention to motorists in order to compensate their distraction.

Nice article and I think you gave a very accurate overview about every junction type as I’ve been cycling in the whole NL, London as well as Copenhagen.

LikeLike

Sharks teeth are great. In the UK the give way markings are a mess. We have about 4 more or different types of markings for giving way in different situations, t-junctions, roundabouts, mini roundabouts and zebra crossings, maybe more. The most common thick double dashed lines, sharks teeth appear to be used in all situations and are much more space efficient. We should just start using them for all.

LikeLike

Absolutely.

Wouldn’t it be amazing if a high-level conversation about how to adapt UK roads could take place… rather than leaving designs to adapt at the speed of a glacier (based on incremental tiny technical changes, none of which can look much different to what’s come before). It ought to be possible to actually do something to actively drive designs ahead. That’s a political not a technical question of course… but unfortunately it looks to the politicians (I suspect) like it’s a technical one…

LikeLike

I’m from Germany, too. I don’t get killed in traffic very often, so I can’t confirm what Florian says. Normally cars turning right wait for pedestrians and cyclists.

In Germany, when a cyclist turns left, her may leave the cyclists lane and turn left with the cars. So he needs to wait for green only once.

LikeLike

Thanks Ralph.

It’s interesting that in Britain we have a rule which means that people driving into a side road should wait for anyone crossing the road. This seems to be a similar rule to other places like Germany. BUT nobody follows the rule.

LikeLike

The way I understand that rule is that you the driver needs to wait for those already crossing the road, which is explained as “already on the road”. The Dutch rule for this is very similar, but is “wait for those who clearly intend to cross the road”, including those still on the footway but walking towards the kerb.

LikeLike

Here in Amsterdam as well as other European towns it’s very common for right turning traffic to share a green with forward cycles and pedestrians meaning the car has to give way to both the cycle stream and the marked pedestrian crossing. It’s an integral part of the signalling system. In the UK there is the (little known) rule of giving way to pedestrians already crossing but this refers to turning into a side street and peds just crossing a road. Here you are actually turning right into a marked light controlled crossing and cycleway, which all receive a simultaneous green. The car just has to wait until both are clear.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The Dutch rule is: traffic leaving the road gives way to traffic staying on that road. This is the same rule you apply when you’re turning left and wait for oncoming traffic to pass, it just also applies to bike traffic going straight on while you (motorist) intend to turn right (or left, even across a bidirectional bike track).

Of course on major junctions with traffic lights, bikes & pedestrians usually have their own green phase, meaning no motor traffic is allowed to cross their path (no right turns on red!).

In addition to that, there is, like MV says, the rule that you let people finish crossing the road when they’re already doing that.

LikeLike

I tend to think that in Britain we’ve ended up with something uniquely (?) British in regard to the various rules and conventions and habits. Because we’re quite keen on people sticking to the rules we end up feeling that those who don’t stick to the rules should be punished. We combine this with giving the person who feels wronged some power over the other person (because they are driving) and what we get isn’t pretty.

What can be seen in every British town and city is that when someone walks or cycles in a place where they are seen to be in the wrong – or even where they are seen to be foolish – people often respond dangerously. Whereas elsewhere they go around the person who is in the way, or they wait, here they drive AT the person in order to teach them their mistake.

That’s an incredibly ugly result of our way of thinking.

I once (very long ago when I was young) was given a formal warning from work for swearing at a colleague. He was driving a minibus with passengers (including me) and had intentionally driven close by a teenage boy who was walking on the road. It was clear that his intention was to frighten the boy to show him that he shouldn’t have been on the road. At the last minute the boy stepped further into the road and avoided death/injury only by a few centimeters. I said ‘bad’ things to my colleague. I think that he was gently warned for his behaviour – but I’ve never forgotten that I also got in trouble for swearing at him. When you reflect on this it indicates a deeply skewed understanding of priorities.

Does this behaviour exist elsewhere?

LikeLiked by 1 person

The ‘Dutch’ junction example you pick out is not so much a specific template but rather what falls out of choices made about protected cycleways and the relationship with other elements of the street. Starting with the assumption that there will be a footway, a cycleway and a carriageway, and that there will be a protective verge of some sort between the carriageway and the cycleway. Draw the path of travel of each type of user through the junction, straightforwardly. Then you naturally arrive at the design with 4 cycleway-junctions at the corners of the carriageway-junction. The famous ‘corner islands’ are just negative space — not explicit features — but rather the remnants of a verge that is cut in two directions, still performing its protective functionality.

If you expect right-turning cars to proceed at the same time as straight-moving cycles then some space is made for staging by pulling the cycleway to the right a bit. Or if the junction is simultaneous-green then the path of travel of people cycling will head directly towards the junction centre.

The verge-separated cycleway depends upon the fact that people cycling don’t need traffic signals at purely cycling junctions; people are very good at sorting themselves out through negotiation. Ideally what you want is priority given to the direction that currently has the corresponding green light at the junction. This is generally pretty obvious when you’re there in person. Although very busy places do struggle with overflow so they’re trying various interventions such as ‘yellow boxes’ and ‘swarm-proofing’ by expanding the waiting space into the verge.

LikeLike

Matthew – that’s a really helpful way to explain the system. I wish I’d written that 🙂

Thanks.

LikeLike

One other difference that might be worth pointing out in a following article is that in the Netherlands, at a junction with lights it’s not common that there are “conflicting greens”. Which is to say, if in NL there is a lane for traffic turning left, and it has a green light, the traffic on the opposite side will have a red light. In the UK it seems very common that traffic turning right has to wait in the junction for a gap in the oncoming traffic.

I think usually that also extends to the cycle track. Where you mention that drivers turning right would have to give priority to cyclists, I think that it’s much more common for there to be no conflict at all, because cyclists wouldn’t have a green at that time. However, most of my experience cycling is with my hometown Groningen, which has a concept of “cyclists green together”, so I’m not going to say you were wrong in this respect, Groningen might just be uncommon in this area.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great extra detail – thanks. I realised as I started to write this blog article that I couldn’t put all the detail in (not least because of hitting the limits of my knowledge). That’s a good addition.

LikeLike

Its not very common in the UK now though, it was years ago. In the UK at a junction where a solid green light is lit, you can go straight, left or right. If you are turning right you have to give way to opposing straight traffic. If a green right arrow is lit then its a free right turn, traffic will not be moving the other way, no need to give way. Unlike the majority of countries red and amber arrows are not permitted in the UK, only green, therefore green straight arrows at the same time as a solid red light are used if right or left turns need to be prevented, resulting in a forest of lights at junctions. Why we can’t have red and amber arrows I don’t know.

However I have never seen any new or revamped junctions that use solid green lights, always now individual green arrows for each direction, no conflicting greens as they are not safe. It is only older junctions that are like that, there may be still some but not that I know of.

LikeLike

The sharks teeth for the Dutch junction are not in the right place for the majority. They appear to be most commonly placed when entering the junction on the cycle tracks like this: https://goo.gl/maps/E4K3kQvseRS2

Rather than placing them at the point where people have just finished crossing, which makes better sense to me as in your diagram it might result with cyclists being left stranded in the road, especially if flows on the track are high. Safer to have to wait on the track.

LikeLike

David that’s a good example of the shark’s teeth being used differently. I think that one thing I learned by working through various junction designs on Streetview (which is easier than doing it during a trip with people waiting for me) is that the sharks teeth are used all over the place. That, I guess, is what makes them so valuable. They aren’t just a standard feature meaning that you know that one road gives way to another. Instead they are used to explain (clearly) very fine details for one user over another.

LikeLike

A very good read about the different perspectives on cycling ( I might mix in some comment on Part 1). I am German and live in Göttingen, one of the cities considered to be quite friendly to cyclists and it is very interesting to compare the streets I see every day to the different traffic concepts and how well they are implemented in comparison to benchmark cities like Amsterdam and Copenhagen.

In my opinion, German cities are focussed far too much on motorized traffic, but at least in Göttingen, a lot of major streets follow the ideas of your Copenhagen Design, with the difference, that cycle tracks are rarely separated from footway by a kerb but there usually is a colour code. Junctions however are too often a lot more like the British model, which gets worse, because most drivers don’t realise, that cyclists have equal rights in those spaces. I always get the impression, that with the desolate condition of cycle tracks, the frequent manhole covers on cycle tracks and constant bumps through lowered kerbs, that none of the city planners actually ride their bike on the streets they design…

LikeLike

Hi Chris.

I’m pleased to say that I’ve cycled in Göttingen, and with my family too (the kids were roughly around 5 years old). It’s a while ago now though.

As far as I remember we managed to stay away from the roads, but that might have been because we were doing a leisure trip and not trying to get anywhere important. If I remember clearly I think that we cycled to the area where the large swimming pool is. Do I remember that there are many paths suitable for leisure cycling – away from the roads completely – but less to support people on the roads themselves?

I think I should look at some photographs to remind myself.

I do remember that cycling was much better supported than here though.

And Google Streetview doesn’t cover Göttingen does it?

LikeLike

Yeah, Streetview in Germany is still a bit of a problem, because of weird concerns about privacy, but there are some snapshots.

Göttingen is split concerning the cycling support. There are a growing number of cycle tracks in and around the city for leisure, especially, if you are okay with gravel tracks (which I am not). In the city centre cars are mostly forbidden anyway, so no further support is really needed and there is one path northwards and one southwards for public transport and cycling. The special treat for cycling is the connection between the station and the university, where there is a two way cycle highway, a 2 metre wide cycle tracks along the major streets(I even found a snapshot or two: https://goo.glmaps/JB1d7a1Fo7S2 ; https://goo.gl/maps/iNBKtbExhfE2). Additionally the cycling traffic is routed through residential area, so other than the cyclists only residents are allowed to drive to their home in those places.

As I said before, on major streets the concept is much alike the Copenhagen model, but every other street is directly considered residential and therefore rarely any support for cycling. Even though Göttingen is much smaller than the other cities mentioned, my experiences in Dresden are similar in regards to the ratio of supported streets and residential streets that expect you to ride on the street. The biggest problem is consistency. At the station the cycle highway just ends and this end is often blocked by parking cars. But hopefully the good ideas will spread in the future.

LikeLike

Thanks – those are helpful Google links. Actually in some ways that looks more like a glorified (done very well) version of what we often get in the UK – more than it looks like Copenhagen to me. Copenhagen always seemed to separate walking and cycling with a (small) kerb. The UK does the paint-on-footway thing… just not so convincingly as I see in Göttingen.

I don’t remember that cycleway. Thinking of it it’s probably 10 years or so since I was there. Is it newer than that – or did I just not go that way?

LikeLike

Since I only live here for two years, I had to look it up, but the “Radschnellweg” was built between 2013 and 2015 and is supposed to be extended in the coming years. With my comparison to Copenhagen I didn’t mean the distinct separation, but rather the concept of one way cycling tracks on either side of the street. Even with the Radschnellweg being two directional, there usually is a one way cycle track on the other side of the street. I would say, that generally in Germany cycle tracks are only colour coded

LikeLiked by 1 person

I see the blue lines indicating the cycleway – is that standard then? Is blue the normal colour? And is it always in this way – with lines along the edge of the cycleway – and can I see this in other cities?

LikeLike

No, the blue lines are special, I guess to match the blue signs that mark the Autobahn. The standard colour code is red and not with lines, but coloured pavement. Although there certainly are a lot of exceptions, where cycle tracks are just a different shade of grey (I found a good example for the average cycle track in Germany, I think : https://goo.gl/maps/BKSnK6AmQoF2). Other cities also adapt the concept of cycle highways, especially the new Berlin government, which presented a concept of improved cycle infrastructure with wider, possibly uninterrupted cycle tracks to promote cycling even for longer inner city distances (sadly only in German, not in the English version of the site, but you can see the proposed maps: https://www.berlin.de/senuvk/verkehr/politik_planung/rad/schnellverbindungen/index.shtml). But it takes time and cycling is still much less promoted in the south of Germany, due to it being more hilly and a stronger car lobby, which was particularly active in the seventies, when those cities where developped.

LikeLike

Another helpful Streetview link – thank you.

There is an idea that I haven’t managed to write about yet – which is that some countries treat people cycling as pedestrians on wheels (expected to mix with pedestrians), and some as vulnerable vehicles (expected to mix with motor traffic, but with some protection). But only the Netherlands seems to have properly understood that those cycling represent a third separate category of road users.

The Streetview links you’ve provided show the ‘pedestrians on wheels’ way of thinking.

Most/many of the Netherlands cycle tracks are like mini roads – clearly separate from the footway, but not part of the main section of roadway. People on foot clearly have to cross this like it’s a mini road (which is usually very easy).

Copenhagen has done something very different I think. Cycling there I feel like I am seen as part of the motor traffic… so separated for protection for some of the time, but expected to join in with the motor traffic whenever I get to a junction.

Maybe this needs to go into part 3.

LikeLike

I agree with the idea of those different perspectives and I think the missing consideration of all three parties in our city planning is the general problem for cyclists, as they are always the smallest group.

I am looking forward to part 3 🙂

LikeLike

Love the article! I’m looking forward to Part 3.

One thing that I will mention is that for major roads, quite often in NL we will get grade separated junctions where similar roads in DK or UK we would not.

LikeLike

Yes. There’s another thing that I haven’t quite managed to write about (or finish thinking about) which is that major (very large) roads seem to be kept separate from the surrounding human life in many ways. So I note that making my way back into Utrecht we passed under or over a number of major roads – probably motorways – but because the surrounding infrastructure was still at a human scale they weren’t such a problem. What I mean is that in the UK as you approach a motorway the roads get larger and larger… so it isn’t only the motorway that you have to negotiate, but the surrounding motorway-like roads. In the Netherlands I felt more like we were on more human-scale roads even as we approached the major road – passing under/over it on more human-scale roads.

I know that I’m not being very clear – but there’s something going on there I think. I may be wrong too – at this stage this is just my impression.

LikeLike